FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

Written and Edited by Jody Segrave-Daly, RN, IBCLc, LYnnette HAFKEN, MA, IBCLC and Christie del Castillo-Hegyi, MD

Our goal is to respond to the many statements that have been made about the Fed is Best Foundation and to answer questions we receive about what the Foundation stands for. Unfortunately, our #FedIsBest phrase has been used incorrectly by others, and it’s important that we clarify what it means and doesn’t mean

6. Does the FIBF believe all exclusively breastfed babies need supplementation before the onset of mature milk?

No, and we never have.

As health care providers, we have an ethical and moral obligation to fully inform mothers of both the benefits and risks of exclusive breastfeeding when promoting exclusive breastfeeding. The high rates of delayed onset of lactogenesis II, as well as conditions that cause a poor transfer of breast milk, carry serious risks to exclusively breastfed newborns, as they depend on daily increases in calories and fluids until mature milk arrives on day three.

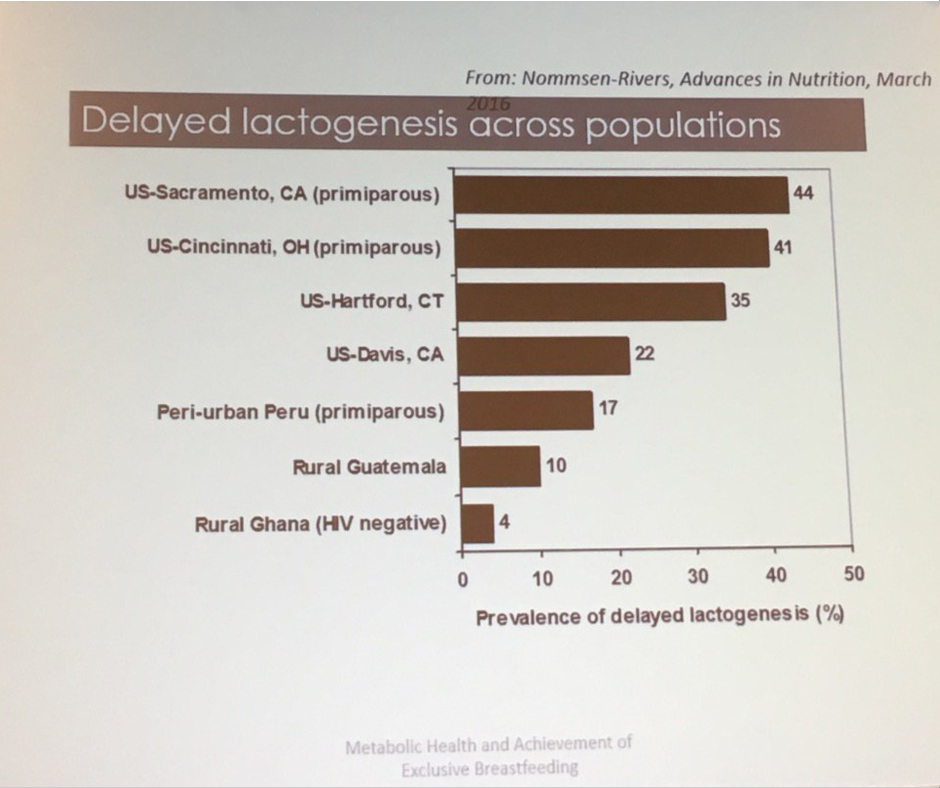

The current research tells us the actual rates of adequate breast milk production are unknown and the current estimates for lactation disruption range from 12-15% or one in eight mothers. We are learning that mothers are experiencing delayed lactogenesis II (onset of full milk supply greater than 72 hours post-birth) commonly, for complex biological and other unknown reasons. However, the fact that something is common does not mean it is normal or ideal.

Nommsen-Rivers, Percent of mothers experiencing delayed copious milk production. Presented at 2017 ABM conference

The scientific studies show that delayed onset of lactogenesis II (DOLII), lactation dysfunction and low milk supply (LMS) are common.

Twenty-two percent of mothers experience delayed onset of milk production, which increases the risk of excessive weight loss (>10%) in their newborns seven-fold (Dewey et al., 2003). Delayed onset of lactogenesis II (DOLII) was most common among first-time mothers, mothers with high BMI, and other factors that increased the risk of ineffective breastfeeding.

Delayed onset of lactogenesis II also occurred commonly outside of the U.S. as found in this study from a Brazilian Baby-Friendly Hospital showing it occurred to 19% or almost 1 in 5 mothers. (de Oliveria Rocha et al., 2019)

Another study of first-time mothers showed that an astounding 44% experienced delayed onset of lactogenesis II. (Nommsen-Rivers, et al. 2010). The primary risk factors for DOLII were:

-

-

- maternal age ≥30 years old

- body mass index in the overweight or obese range

- birth weight >3600 g

- absence of nipple discomfort between 0–3 d postpartum

- infant failing to “breastfeed well” ≥2 times in the first 24 h

-

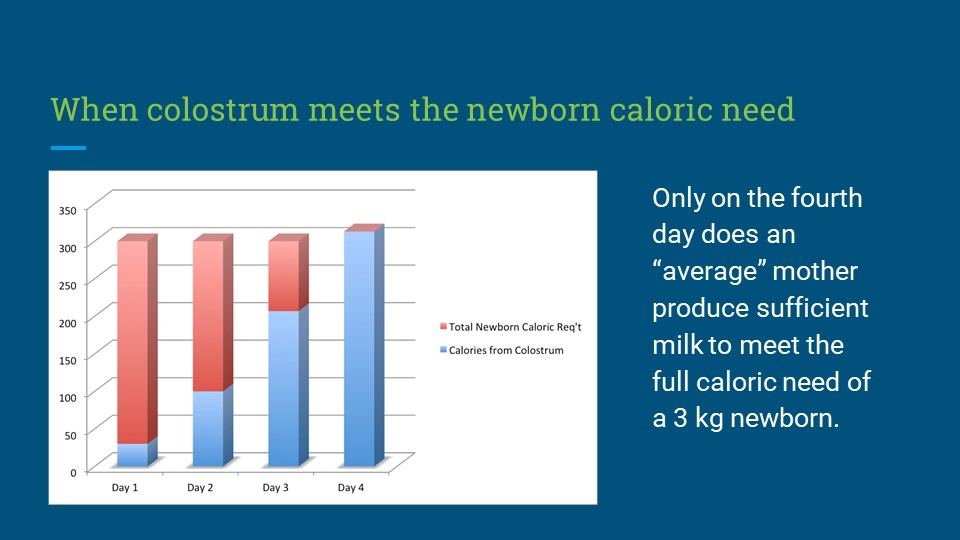

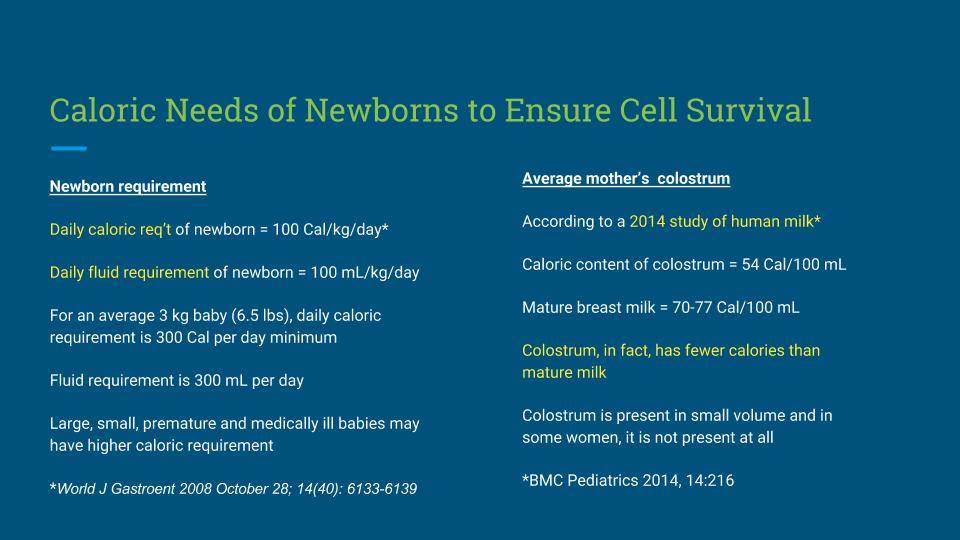

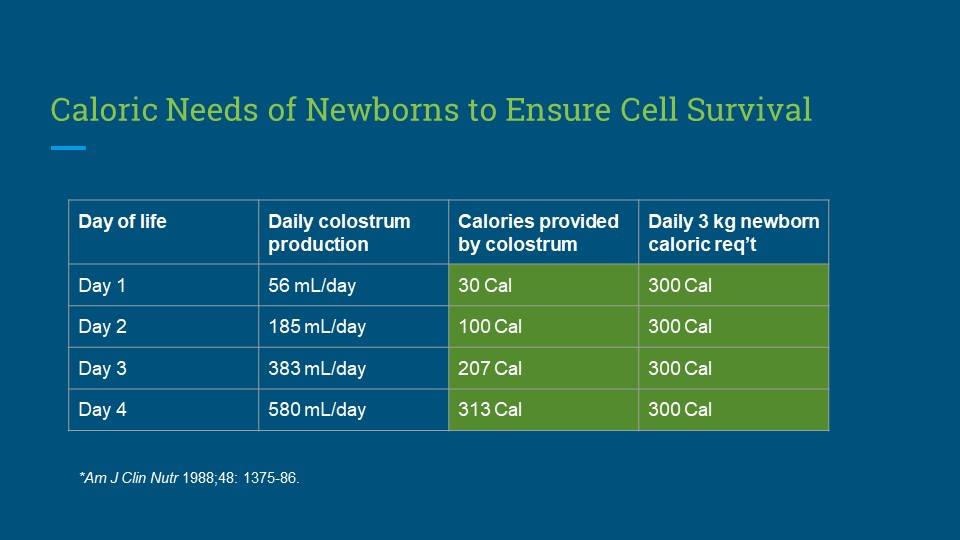

Colostrum Calories

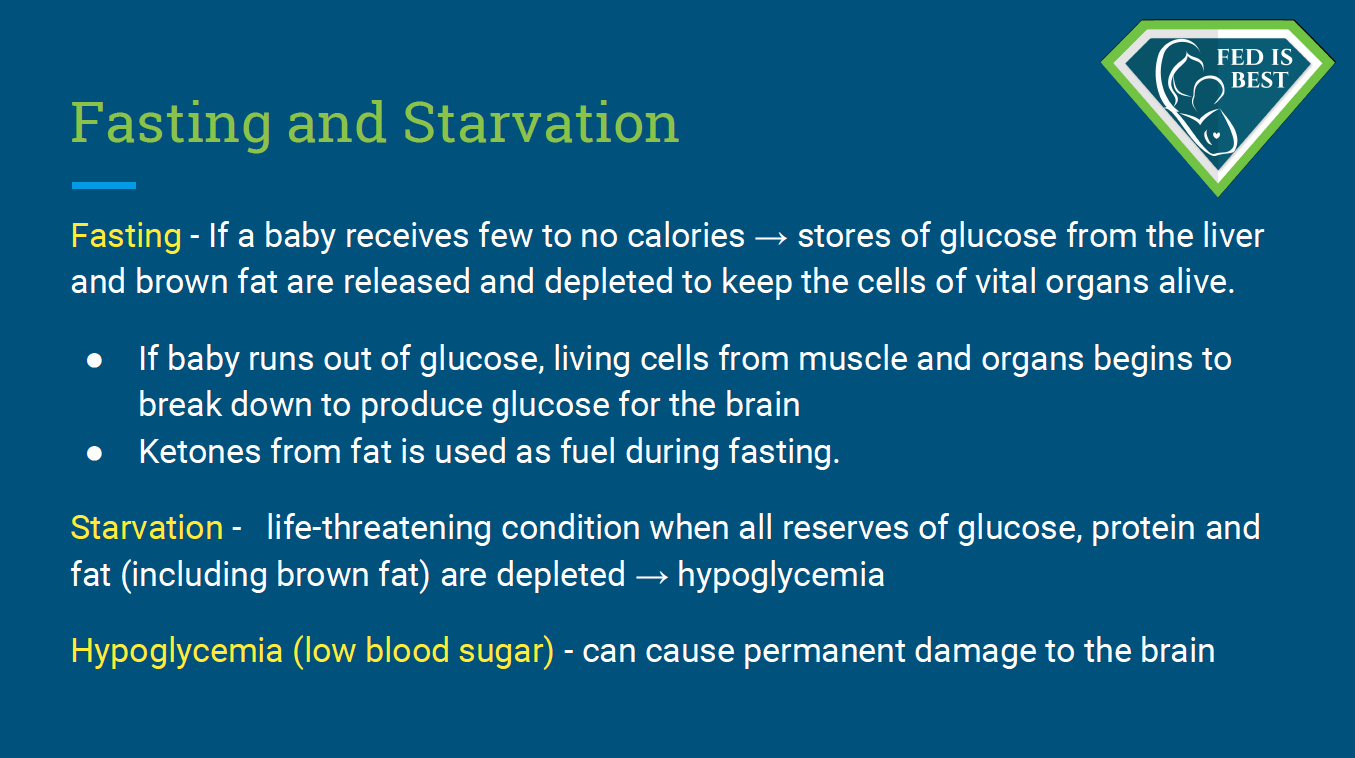

The scientific literature shows that colostrum, in fact, has fewer calories, containing 54 Calories/100 mL compared to 66-77 Calories/100 mL in mature breast milk (Gidrewicz and Fenton, 2014). Therefore, in the period before lactogenesis II, an exclusively colostrum-fed newborn is “fasting,” meaning that the baby is consuming fewer calories than she is expending, causing weight loss. Babies are dependant on their metabolic reserves until the onset of copious milk production. However, some babies do not have enough reserves and this can result in acute starvation-related complications. These complications can result in irreversible impairments in brain development. The term “starvation” is not intended to be inflammatory; it is a medically accurate diagnosis, the definition of which is explained below.

Complications From Insufficient Breast Milk Research:

- Research has shown that among healthy term newborns who are discharged from the hospital, exclusively breastfed newborns are twice as likely to be readmitted to the hospital, most commonly for hyperbilirubinemia and dehydration. They are also more likely to require more follow-up visits with their pediatricians for concerns related to feeding and adequate weight gain. (Flaherman et al., 2018).

- A study from the U.K. showed that among healthy term and near-term newborns, exclusive breastfeeding at discharge doubled the risk for readmission for hypoglycemia (Dassios et al, 2018).

- According to a review published in the Journal Of Family Practice in June 2018, “exclusive breastfeeding at discharge from the hospital is likely the single greatest risk factor for hospital readmission in newborns. Term infants who are exclusively breastfed are more likely to be hospitalized compared to formula-fed or mixed-fed infants, due to hyperbilirubinemia, dehydration, hypernatremia, and weight loss.” They estimated that for every 71 infants that are exclusively breastfed, one is hospitalized for serious feeding complications.

Beyond the first days of life, low breast milk production and the inability to produce a full milk supply are common.

- Data from the Infant Feeding Practices Study showed that 12% or one in eight women were unable to maintain a breastfeeding relationship for the first year of life. Those most commonly affected were women with high BMIs and women with high depression symptoms (although it is unclear whether the depression is the cause or the effect of failed lactation; Stuebe et al., 2014).

- The largest study ever done to measure actual breast milk production was done by Kent et al. in 2016 following 116 breastfeeding mothers with and without breastfeeding problems. The mothers measured all the breast milk they fed their infants over the first month of life through direct feeding (using weighted feeds) and expressed breast milk feeding. This study found that between days 11 and 13, 2/3rd of the mothers could not produce more than the minimum 440 mL required to feed their infant exclusively and between 14 and 28 days, nearly 1/3rd could not produce that minimum.

- Dr. Marianne Neifert, Clinical Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine, co-authored a 1990 study of 319 breastfeeding primiparous (first-time) mothers and found 15% were unable to produce sufficient milk by three weeks after delivery despite intensive lactation support.

- In a study of 1065 mothers, 532 or 50% had breastfeeding-related problems. Thirty-one percent affected the mother (e.g., engorgement, fissures, low milk supply, infections, breastfeeding cessation), and 10% affected the newborn (poor suction, neonatal jaundice, pathological weight loss, need for hospital admission). Nine percent affected both the mother and the newborn (Govonni, Richi, 2019). Among the identified risk factors for breastfeeding problems, operative vaginal deliveries and cesarean delivery had the highest associated risk for breastfeeding problems. Other factors like higher maternal age, number of previous deliveries, and lower Apgar scores also increased the risk of DOLII.

- Dr. Shannon Kelleher talks about these staggering numbers in her publication, “Biological underpinnings of breastfeeding challenges: the role of genetics, diet, and environment on lactation physiology,” in which she says the prevalence of lactation insufficiency may be much higher, as women internationally cited that their baby was “not satisfied with breast milk” as the primary reasons for weaning prior to 6 months.

Listening to Mothers

The data show that maternal perception of insufficient breast milk and the onset of lactogenesis II is in fact accurate. Listening to the mother instead of encouraging her to distrust her own instincts is critical to helping her reach her breastfeeding goals and maintaining her confidence.

- The study called “Maternal Perception of the Onset of Lactation Is a Valid, Public Health Indicator of Lactogenesis Stage II” showed that maternal perception of onset of lactogenesis II (including cases when they are delayed) is valid. Since small volumes of colostrum cannot sustain an infant long-term and prolonged exclusive colostrum feeding can result in complications, maternal perception of onset of copious milk production can be used to determine whether or not an infant’s signs of distress are due to persistent hunger. Infants showing distress before the onset of lactogenesis II are at high risk for feeding complications.

- A 2017 study by Murase et al. called “The Relation between Breast Milk Sodium to Potassium Ratio and Maternal Report of a Milk Supply Concern” showed that maternal perception of insufficient milk supply was valid and predicted actual low milk volumes as measured by the sodium and potassium levels of their breast milk.

Supplementation Studies

Despite the lack of evidence using the gold-standard of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showing that supplementation interferes with breastfeeding, health professionals and parents continue to be taught to avoid supplementation until an infant has developed or is at serious risk of insufficient feeding complications. In fact, six RCT studies have shown that in infants with weight loss above the 75th percentile, judicious supplementation with 10 mL (two teaspoons) of donor breast or formula milk after nursing had no effect on long-term breastfeeding, one showing it prevented hospital readmissions in all of the supplemented newborns.

- Limited Amount of Formula May Facilitate Breastfeeding: Randomized, Controlled Trial to Compare Standard Clinical Practice versus Limited Supplemental Feeding

- The Effect of Early Limited Formula on Breastfeeding, Readmission, and Intestinal Microbiota: A Randomized Clinical Trial

- Limited Amount of Formula May Facilitate Breastfeeding: Randomized, Controlled Trial to Compare Standard Clinical Practice versus Limited Supplemental Feeding

- Effect of Donor Milk Supplementation on Breastfeeding Outcomes in Term Newborns: A Randomized Controlled Trial

- Effect of Early Limited Formula on Breastfeeding Duration in the First Year of Life

- In-hospital formula supplementation and breastfeeding initiation in infants born to women with pregestational diabetes mellitus

Dr. Flaherman’s research suggests that it is not simply early supplementation that affects breastfeeding outcome, but the volume, delivery mode, and rationale for use that are important. She also suggests that reverse causation may be a factor in breastfeeding cessation in that breastfeeding problems lead to formula use, rather than formula use causing breastfeeding problems. Concerns about limited amounts of formula sensitizing the infant‘s “virgin gut” are speculative and pale in comparison to the risk of brain damage from insufficient food and fluids.

It is unconscionable to scare mothers into withholding supplements while not disclosing the risks of insufficient milk. Would we be even having this conversation if banked donor milk were available for all babies who needed temporary supplementation?

Because of this research, it’s imperative to assess each mother and baby to identify potential individual risk factors for delayed onset of lactogenesis II or low milk supply. This will help the health care team offer timely, temporary supplemental nutrition with banked donor milk or formula milk to prevent complications while providing optimal lactation management and support for identified high-risk dyads. Additionally, the health care team can identify scant or absent colostrum in a high-risk mother through instruction on the manual expression of colostrum.

A comprehensive clinical exam/assessment by the pediatrician, nurse, and lactation consultant care team is necessary every eight hours to evaluate every newborn for safe and adequate intake while breastfeeding, and the mother’s observations should be part of the evaluation. The pediatrician, nurse, LC, and parents should have clearly defined roles in the treatment plan.

The health care team should be evaluating the newborn for:

- signs of hypoglycemia

- ineffective latch or transfer

- excessive weight loss percentage

- bilirubin (jaundice) levels

- persistent hunger cues

- oral anomalies

- lethargy or excessive sleepiness

- dehydration/hypernatremia

- stable vital signs

- the persistent presence of red urate crystals in diapers (longer than 2-3 days) and diaper counts after copious milk production has occurred

All of the clinical markers must be within normal limits for a baby to be considered adequately fed.

The question is, how many randomized, controlled studies support Step 6 of the WHO’s Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding to avoid supplementation from birth in order to improve breastfeeding outcomes? None. Absolutely none.

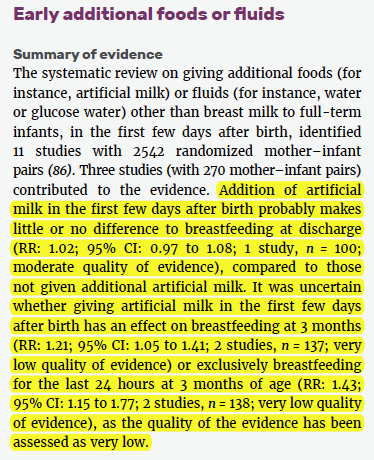

In 2017, the World Health Organization published its guidelines updating its recommendations for “Protecting, Promoting and Supporting Breastfeeding in Facilities Providing Maternity and Newborn Services,” which outlines the evidence for the WHO recommendations on breastfeeding support for newborns in health facilities based on the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding. Here is the evidence presented to justify the recommendation to avoid supplementation in breastfed newborns.

From the World Health Organization

How did the very low quality of evidence turn into moderate-quality evidence for exclusive breastfeeding, particularly when the evidence showed improvement of breastfeeding rates in supplemented breastfed newborns?

Continue with FAQs Part 3 below:

https://fedisbest.org/2019/10/do-you-believe-exclusive-breastfeeding-is-a-good-goal-to-promote-faqs-part-3/

FAQs Part 1:

FAQs Part 1: The Most Common Questions Answered At The Fed Is Best Foundation

How to safely breastfeed:

One thought on “FAQs Part 2: Does The Fed Is Best Foundation Believe All Exclusively Breastfed Babies Need Supplementation?”