Written by Jody Segrave-Daly MS, RN, IBCLC

As a veteran neonatal nurse and lactation consultant, parents often ask me how the antibodies found in breast/human milk work to protect their babies. Published research on immunology is highly technical and difficult to understand, and unfortunately, the readily available information (especially on social media) contains a lot of false and conflicting information. So, I’m here to share evidence-based information about this important topic in a way that is easier for most parents to understand.

How does the immune system work?

Our immune system is very complex, but generally speaking; it is responsible for fighting off both germs that enter our bodies from our environment and also for protecting us from diseases like cancer that occur within our bodies. I will be focusing on how the immune system fights off germs, which it does by producing antibodies.

What is an antibody, and what does it do?

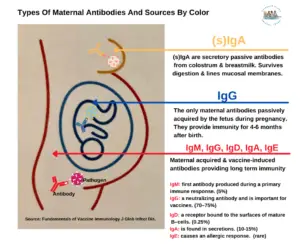

An antibody is a protein produced by the body’s immune system when it detects the surfaces of foreign and potentially harmful substances, also known as pathogens. Examples of pathogens are bacteria, fungi, and viruses, all microorganisms. The antibody response is specific; it will seek and neutralize the microorganism and stop the invasion. There are five classes of antibodies: IgM, IgG, IgA, IgD, and IgE.

There are two ways babies acquire and develop immunity:

- The first way is through passive immunity (temporary)

- The second way is through active or acquired immunity (lifelong)

The color denotes where the antibody source originates from in the body.

Passive Immunity During Pregnancy

The first way for a baby to acquire immunity is called passive immunity, and it occurs during pregnancy. Over a mother’s lifetime, she is exposed to many different pathogens, and her immune system develops the ability to produce a large catalog of antibodies that can act against them. During pregnancy, these antibodies are transported across the placenta to the fetus’s blood supply. These types of antibodies are called immunoglobulin G or IgG. They are the only antibody type that passes through the placenta to the growing fetus. They are called passive maternal IgGs because of how they are transferred to the baby.

IgGs are the most common type of antibody in our bodies. They help protect us, as well as our unborn babies, from viral and bacterial illnesses. Human babies are born with all of the passive maternal IgG antibodies their mother has during pregnancy.

To provide additional, critical passive IgG antibodies that will pass from the placenta directly to the baby’s bloodstream, mothers should strongly consider following the vaccination recommendations during pregnancy. This will help protect the baby from infections such as pertussis (whooping cough), influenza, COVID, RSV, and other illnesses ahead of their scheduled childhood vaccinations and before their immature and vulnerable immune system begins to produce its own antibodies.

Women vaccinated during pregnancy pass protective antibodies to babies (CDC.gov)

Maternal IgG antibodies are temporary and gradually disappear within four to six months after birth. Fortunately, immediately after birth, the baby begins to make their own IgG antibodies in response to viruses and bacteria in their environment and through childhood vaccinations. The immune system is constantly maturing, but children under two are most vulnerable. By five years of age, children have been exposed to many viruses and bacteria and received many vital vaccinations; therefore, they are less vulnerable to serious infections. Premature babies are particularly vulnerable, as they don’t receive the 40 weeks gestation time to receive the full maternal passive immunity that a term baby does. (Most antibodies are transferred in the last four to six weeks of pregnancy.) Maternal IgG antibodies passed through the placenta are very effective in protecting neonates and infants against most infectious diseases. This is why term human babies can be fed properly prepared formula and thrive without the passive immunity that breast milk provides. Evidence has shown, however, that human breast milk, whether through direct breastfeeding, expressed breast milk, or human donor milk, is critical to preterm babies as it reduces the risk of developing sepsis and a deadly infection called necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), which affects a baby’s intestines.

Passive Immunity Through Breastfeeding

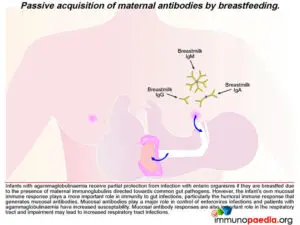

The other way a baby can acquire passive immunity is through breast/human milk. Colostrum is the first milk a woman produces when she begins to breastfeed, and it contains many antibodies called secretory immunoglobulins (You’ll see this abbreviated as sIgA.) Over 90% of the antibodies are sIgA. IgM and IgG antibodies are also present in tiny amounts. These sIgA antibodies in human milk line the mucous membranes in the baby’s mouth, upper airway, throat, ears, and intestines; here, they guard against germs entering the mucosal lining, which is the first port of germ entry, by neutralizing the pathogen. Secretory IgA antibodies can survive being broken down by gastric acid and digestive enzymes in the stomach and intestines. Human babies cannot directly absorb these passive maternal antibodies from colostrum or breast milk into their bloodstream. Instead, the sIgA antibodies protect against infections by working inside the baby’s gastrointestinal tract and respiratory system.

This passive breastfeeding sIgA immunity is dose-dependent, meaning the more feedings/or doses of breastmilk your baby receives, the more protection they have. The dose-dependent protection continues until the baby is weaned. This passive immunity is invaluable for premature newborns and newborns born in impoverished countries where there is limited access to clean water for safe formula preparation, often leading to severe diarrhea and death.

Breast milk immunity offers passive protection from respiratory and gastrointestinal illnesses; this does not mean prevention.

However, breastfed babies can still get sick because breastmilk does not prevent respiratory infections, and young children get lots of colds, some as many as eight to ten each year before they turn two years old. For mothers who don’t plan on breastfeeding exclusively for the first six months, breastfeeding during the first months is still beneficial, because this is when the baby’s immune system is the most vulnerable. Human milk also contains infection-fighting components that are not antibodies. (*see the full description below )

The second way a baby develops immunity is by ACTIVE OR ACQUIRED IMMUNITY (germ exposure and vaccination)

A baby’s immune system is at its most vulnerable right after birth. Since passive immunity from both IgG and IgA forms of maternal immunity is temporary, and breast milk antibodies can only protect the respiratory and GI tracts while breastfeeding occurs, these measures are insufficient to fully protect a baby from infectious diseases. At six months, a baby’s IgG antibodies acquired passively from their mother are gone. Their immune systems have started to produce IgG antibodies from the germs they encounter in their world and through vaccinations. This is known as active or acquired immunity, which the body develops after exposure to germs or vaccinations. To continue the protection process, babies need to acquire vaccine-induced immunity, and fortunately, vaccination is a safe and effective way to achieve it by boosting immature immune systems without getting the disease. Active immunity is long-lasting and sometimes lifelong.

Did you know breastfed babies produce higher levels of antibodies in response to some immunizations?

Vaccines are tested again and again to be sure they are safe for children and nursing mothers. If you are concerned about whether or not a particular vaccine is safe to receive while breastfeeding, check the CDC’s list of vaccines that are safe for nursing mothers and babies. Because breastfeeding provides passive antibodies to a baby, breastfeeding is not a substitute for immunization. During the first months before receiving vaccinations, babies are counting on their parents, family, friends, caregivers, doctors, nurses, lactation consultants, and anyone else around them to protect them from diseases they may be unable to fight. Everyone being updated with their recommended vaccines is the best way for a community to support a newborn’s health.

A common question I receive is: “Can I breastfeed while I am sick with the flu?”

The answer is yes, even if you are taking Tamiflu. The flu is not transmitted through breast milk. Breastfeeding can continue while taking precautions to avoid spreading the flu to the baby. The CDC has excellent guidelines about breastfeeding while having the flu.

If a mother is sick, how long does it take for the antibody to be produced in her breast milk?

This picture is one of many popular memes floating around on social media. Unfortunately, the information about the timeline for antibody production is incorrect and misleading.

To be fully informed and to take proper precautions, a mother should know there is a delay between the first exposure to the pathogen and the acquisition of immunity. This process, called the primary response, can take up to fourteen days for optimal antibody production. If a person is exposed to the same pathogen again later, the response is much faster and stronger, called a secondary response.

To provide additional protection for your baby, hand-washing is an excellent way to help prevent the spreading of germs. According to the CDC, “Regular hand-washing, particularly before and after certain activities, is one of the best ways to remove germs, avoid getting sick, and prevent the spread of germs to others.” It’s quick, simple, and keeps us from getting sick. Hand-washing is a win for everyone—except the germs.

Another social media post that went viral is a picture of the color changes of pumped breastmilk from a mother who said her baby was sick. Can this be true?

This study found leukocytes increase when a baby has an active infection, but does that mean a color change occurs? It’s not very likely. Color changes in breast milk are from colorful foods, stages of breastmilk, medication, vitamins, and sometimes from cracked nipples.

What about the back-wash idea in which a baby’s saliva is sucked into valves within the nipple, and the mother’s body produces an immune response that is secreted in her breastmilk.

The idea that a baby’s saliva can trigger changes in breast milk was popularized in 2015, and several mothers have posted viral images and claims similar to the above, but even scientists who study breastmilk say the idea that baby saliva changes breast milk is still a hypothesis that needs to be proven or disproven with high-quality research.

*Please Note: Human milk also contains the following protective components:

- Oligosaccharides and mucins adhere to bacteria and viruses to interfere with their attachment to host cells.

- Lactoferrin binds iron and makes it unavailable to most bacteria.

- B12 binding protein to deprive bacteria of needed vitamin B12.

- Bifidus factor that promotes the growth of Lactobacillus Bifidus, a normal flora in the gastrointestinal tract of infants that crowd out harmful bacteria.

- Fibronectin increases the antimicrobial activity of macrophages and helps repair tissue damage from infection in the gastrointestinal tract.

- Gamma-interferon is a cytokine that enhances the activity of specific immune cells.

- Hormones and growth factors stimulate the baby’s gastrointestinal tract to mature faster and be less susceptible to infection.

- Lysozyme to break down peptidoglycan in bacterial cell walls.

Jody is a champion for debunking pseudoscience in the breast and infant feeding community because parents need to be truly informed when making infant-feeding decisions. She is also a staunch advocate for protecting underfed breastfed babies, and that is why she co-founded the Fed Is Best Foundation. She provides parents with the most up-to-date scientific resources and includes her extensive neonatal nursing knowledge and infant-feeding clinical experiences to help parents make the right infant-feeding decision for the entire family to thrive.

Additional references:

An Introduction to Active Immunity and Passive Immunity

Human milk: Defense against infection.

Infant gut immunity: a preliminary study of IgA associations with breastfeeding.

Mucosal immunity: integration between mother and the breastfed infant

Breast Milk as the Gold Standard for Protective Nutrients

Evolution of the immune system in humans from infancy to old age

Future Research in the Immune System of Human Milk

Breastfeeding and infant illness: a dose-response relationship?

Additional blogs:

An Evaluation Of The Real Benefits And Risks Of Exclusive Breastfeeding.

Feed Your Baby—When Supplementing Saves Breastfeeding and Lives

2 thoughts on “Will Breast Milk Protect My Baby From Getting Sick? Passive Immunity 101”