It was on December 13th at 2:30 in the morning. My water broke as I was sleeping. I woke my husband up and the panic set in. My son was a scheduled C-Section due to the fact he was breech and he was going to be a big baby according to all the scans. I was scheduled for the 18th, which was my birthday, but he decided to come early. My husband and I rushed to St. Joseph’s Hospital in Tacoma, WA. This hospital was a “Baby-Friendly” hospital, which meant they push things like exclusive breastfeeding, no pacifiers, and no nurseries. I didn’t think much of these things at the time, as I was a first-time mom and hadn’t pondered on them much. On paper, this all sounded great, and I was excited to go there. I had a simple birth plan: no circumcision and I wanted my husband in the operating room. That was it really. I trusted the doctors and nurses there to help me out.

Tag: Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative

My Baby Went Through Hell And Suffered Needlessly From Starvation

Jenn T.

My son was born on February 18, 2019. He was 6 lbs 10 oz and had a little trouble regulating his temperature at birth. But after 24 hours, he was okay. I was always told breast was the best way to go. I never breastfed my 9 year old so this was my first experience with it.

My son had latching issues at first and it caused major pain and bleeding. But after latch correction and using nipple shields, the pain dissipated. When we left the hospital, my son weighed 6 lbs (9.3 percent weight loss) and at his checkup the next day, he had gained half an ounce.

At home I was feeding straight from my breasts, every time. My son was content and seemed happy. He smiled and was great the entire time, so I thought. I didn’t pump to see how much milk I had because the hospital where I delivered told me pumping in the first 6 weeks could cause confusion for the baby with latching.

Now fast forward to when he was 21 days old. He had his three week checkup and he was extra sleepy that morning. When we got to the doctor, and not only did he lose weight, (down to 5.5 lbs), but he also had a temperature of 92 degrees. He was hypothermic! So they sent us urgently to the children’s hospital in Nashville. Continue reading

Fed is Best Foundations Statement to USDA Healthy People Goals 2030

Christie del Castillo-Hegyi, M.D.

From December 2018 to January 2019, the Secretary’s Advisory Committee on National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives for 2030 published the proposed Healthy People 2030 Objectives for public comment. Of note, the proposed Healthy People 2030 objectives saw a marked change from the 2020 objectives, namely a reduction of the breastfeeding objectives from 8 goals to one, namely, “Increase the proportion of infants who are breastfed exclusively through 6 months” (MICH-2030-15 ). Among the objectives that were dropped from the list were:

- MICH-23 – Reduce the proportion of breastfed newborns who receive formula supplementation within the first 2 days of life.

- MICH-24 – Increase the proportion of live births that occur in facilities that provide recommended care (i.e. Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative-certified hospitals) for lactating mothers and their babies.

| Healthy People 2020 Objectives | Baseline (%) | Target (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Increase the proportion of infants who are breastfed (MICH 21) | ||

| Ever | 74.0* | 81.9 |

| At 6 months | 43.5* | 60.6 |

| At 1 year | 22.7* | 34.1 |

| Exclusively through 3 months | 33.6* | 46.2 |

| Exclusively through 6 months | 14.1* | 25.5 |

| Increase the proportion of employers that have worksite lactation support programs (MICH 22) | 25† | 38 |

| Reduce the proportion of breastfed newborns who receive formula supplementation within the first 2 days of life (MICH 23) | 24.2* | 14.2 |

| Increase the proportion of live births that occur in facilities that provide recommended care for lactating mothers and their babies (MICH 24) | 2.9‡ | 8.1 |

Exclusive breastfeeding at discharge is a major risk factor for severe jaundice and dehydration. Both conditions can require in-hospital treatment and can result in permanently impaired brain development. Photo Credit: Cerebral Palsy Law

Breast Milk Production in the First Month after Birth of Term Infants

by Christie del Castillo-Hegyi, M.D.

One of the most important duties of the medical profession is to make health recommendations to the public based on verifiable and solid evidence that their recommendations are safe and improve the health of nearly every patient, most especially if the recommendations apply to vulnerable newborns. In order to do this, major health recommendations require extensive research regarding the safety of the real-life application of the recommendation at the minimum.

Multiple health organizations recommend exclusive breastfeeding from birth to 6 months as the ideal form of feeding for all babies under the belief that all but a rare mother can exclusively breastfeed during that time frame without underfeeding or causing fasting or starvation physiology in their baby. In order to suggest that exclusive breastfeeding is ideal for all, if not the majority of babies, one would expect the health organizations to have researched and confirmed that all but a rare mother in fact produce sufficient milk to meet the caloric and fluid requirements of the babies every single day of the 6 months without causing harmful fasting conditions or starvation. There have been few studies on the true daily production of breast milk in breastfeeding mothers. Only two small studies quantified the daily production of exclusively breastfeeding mothers including a study published in 1984, which measured the milk production of 9 mothers, and one in 1988, which measured it in 12 mothers. After extensive review of the scientific literature, it appears the evidence that it is rare for a mother to to not be able to produce enough breast milk to exclusively breastfeed for 6 months is no where to be found. In fact the scientific literature has found quite the opposite.

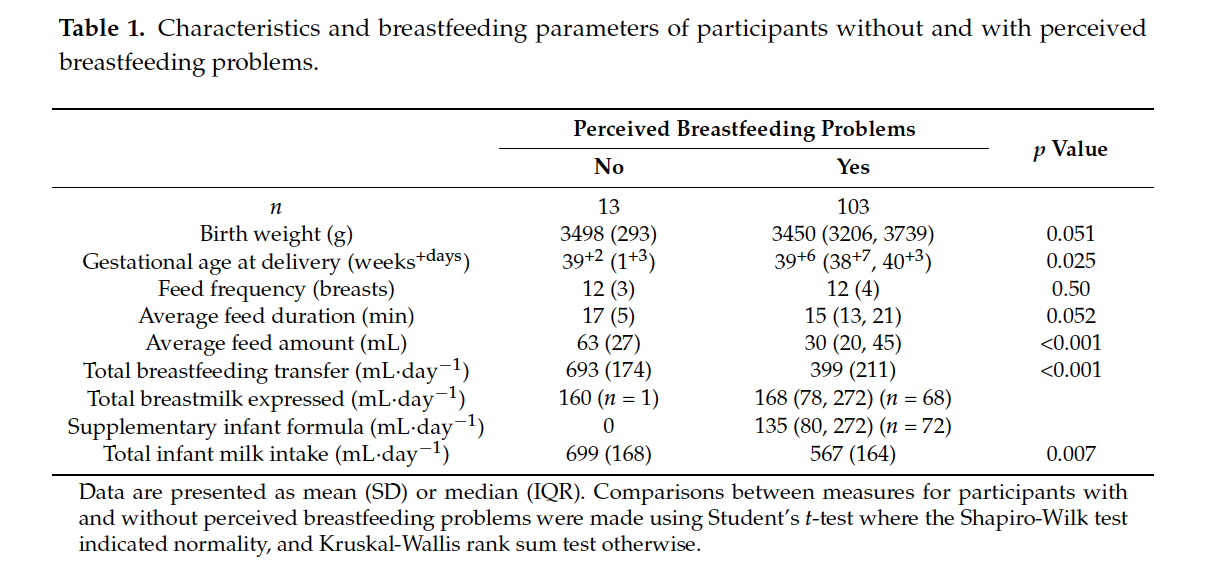

In November 2016, the largest quantitative study of breast milk production in the first 4 week after birth of term infants was published in the journal Nutrients by human milk scientists, Dr. Jacqueline Kent, Dr. Hazel Gardner and Dr. Donna Geddes from the University of Western Australia. They recruited a convenience sample of 116 breastfeeding mothers with and without breastfeeding problems who agreed to do 24 hour milk measurements through weighed and pumped feedings between days 6 and 28 after birth and were loaned accurate clinical-grade digital scales to measure their milk production at home. The participants test weighed their own infants before and after breastfeeding or supplementary feeds and recorded the amounts of breast milk expressed (1 mL = 1 gram). All breast milk transferred to the baby, all breast milk expressed and all supplementary volumes were recorded as well as the duration of each feed.

These were the results…

13 mothers perceived no breastfeeding problems while 103 mothers perceived breastfeeding problems. The most common problem was insufficient milk supply (59 mothers) followed by pain (11 mothers), and positioning/attachment (10 participants). 75 mothers with reported breastfeeding problems were supplementing with expressed breast milk and/or infant formula.

Of the mothers with reported breastfeeding problems, their average weighed feeding volumes were statistically lower than the mothers who did not report breastfeeding problems with an average feed volume of 30 mL vs. 63 mL in the mothers who reported no breastfeeding problems (p<0.001). The daily total volume of breast milk they were able to transfer (or feed directly through breastfeeding) were also statistically lower than those who did not report breastfeeding problems. The moms without breastfeeding problems transferred an average of 693 mL/day while those that reported breastfeeding problems transferred an average of 399 mL/day (p<0.001). The study defined 440 mL of breast milk a day as the minimum required to safely exclusively breastfeed. This is the amount of breast milk that, on average, would be just enough to meet the daily caloric requirement of a 3 kg newborn (at 70 Cal/dL and 100 Cal/kg/day). Babies of mothers with no reported breastfeeding problems were statistically fed more milk than those with breastfeeding problems, 699 mL vs. 567 mL per day (p = 0.007). All 13 mothers who perceived no breastfeeding problems produced and transferred more than the study’s 440 mL cut-off as the volume required to be able to exclusively breastfeed. What this data shows is that a mother’s perception of breastfeeding problems is associated with actual insufficient volume of breast milk fed to her child.

Based on the 440 mL cut-off for “sufficient” breast milk production, some mothers who report their babies not getting enough in fact produced more than 440 mL. However, since 440 mL is the amount of milk that is needed to meet the minimum caloric requirement of a 3 kg newborn, if the mother had a newborn weighing > 3 kg as they would expect to be past the first days of life if growing appropriately, many of the mothers reporting breastfeeding problems may be producing more than 440 mL but are still in fact producing less than the amount to keep their child satisfied and fed enough to grow. A supply of 440 mL would actually be just enough milk to cause a 3 kg newborn to be diagnosed to fail to thrive at 1 month since they would not gain any weight if fed this volume of milk. Failure to thrive has known long-term consequences including lower IQ at 8 years of age. So their conclusion that some mother’s perception of insufficient breast milk may in fact be inaccurate as a volume of 440 mL is in fact “not enough” for most newborns weighing > 3 kg.

Neonatal Nurse Practitioner Speaks Out About The Dangerous Practices Of The BFHI

by Christine K.

When the Fed Is Best Foundation launched two years ago, a few nurses sent us messages about their experiences working in a Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) hospital. They shared common concerns about watching exclusively breastfed babies crying out in hunger from not enough colostrum while being refused supplementation just so that high exclusive breastfeeding rates were met. Two years later, we now receive messages from nurses, physicians, lactation consultants, and other health professionals, regularly. They express their concerns while asking for patient educational resources. They tell us their stories and they need support and direction on what to do about unethical and dangerous practices they are forced to take part in. We collected their stories and are beginning a blog series on health professionals who are now speaking out about the Baby-Friendly Health Initiative (BFHI) and the WHO Ten Steps of Breastfeeding.

Christine K. is a Neonatal Nurse Practitioner currently working in a BFHI Hospital with 25 years of experience. She has worked in both BFHI and non-BFHI hospitals and talks about her concerns about taking care of newborns in the Baby-Friendly setting.

Regarding Unsafe Skin-To-Skin Practices

In BFHI facilities, skin-to-skin is mandated. The protocol calls for skin-to-skin at birth, for the first hour, then ongoing until discharge. New mothers are constantly told that it is important for bonding, for breastfeeding, for milk production and for temperature regulation of the newborn. Baby baths are delayed for skin-to-skin time and nurses are required to document in detail the skin-to-skin start and end times. There is no education on safety regarding skin-to-skin time, only that it is to be done. I have been responsible for the resuscitation of babies who coded while doing skin-to-skin. One died, and the other baby is severely disabled. Mothers are not informed of the risks of constant and unsupervised skin-to-skin time. Mothers have complained to me that they felt forced to do skin-to-skin to warm up their cold or hypoglycemic infant because they are told skin-to-skin time will help their infant resolve these issues when in fact it doesn’t. There is also no assessment of the mother’s comfort level with constant skin-to-skin. It’s very discouraging to hear staff say things like, “That mother refused to do skin-to-skin,” like it was a crime or an act of child abuse. The judgment is harsh on mothers who fail to follow the protocol. I have noticed that partners are pushed to the side, especially in the first hour of life, not being able to hold their newborn, due to this strict policy. Their involvement has been discounted in the name of the exclusive breastfeeding protocol. Continue reading