Written by Hillary Kuzdeba, MPH

Before I had my first baby, I was like so many other health professionals – I believed that breast was best, and that every mother should be encouraged to strive for exclusivity, as recommended by the major medical organizations like the American Academy of Pediatrics and World Health Organization. I prepared diligently for breastfeeding, speaking to lactation consultant co-workers, watching documentaries, reviewing breastfeeding educational resources, and talking with the breastfeeding mothers I knew. My husband and family were all extremely supportive of breastfeeding, because they too knew breast was best. I knew that breastfeeding could be challenging, but I was prepared to make it work. And everyone assured me that it would, as long as I was dedicated.

My daughter was born at 37 weeks, 2 days after a difficult unmedicated labor, and vaginal delivery. She was a tiny little thing, just over 6lbs but she was strong and healthy. She was born with moderate cranial bruising from the almost six hours of pushing it took to get her out. She was immediately put skin to skin, and we had our first nursing session within 20 minutes of her arrival.

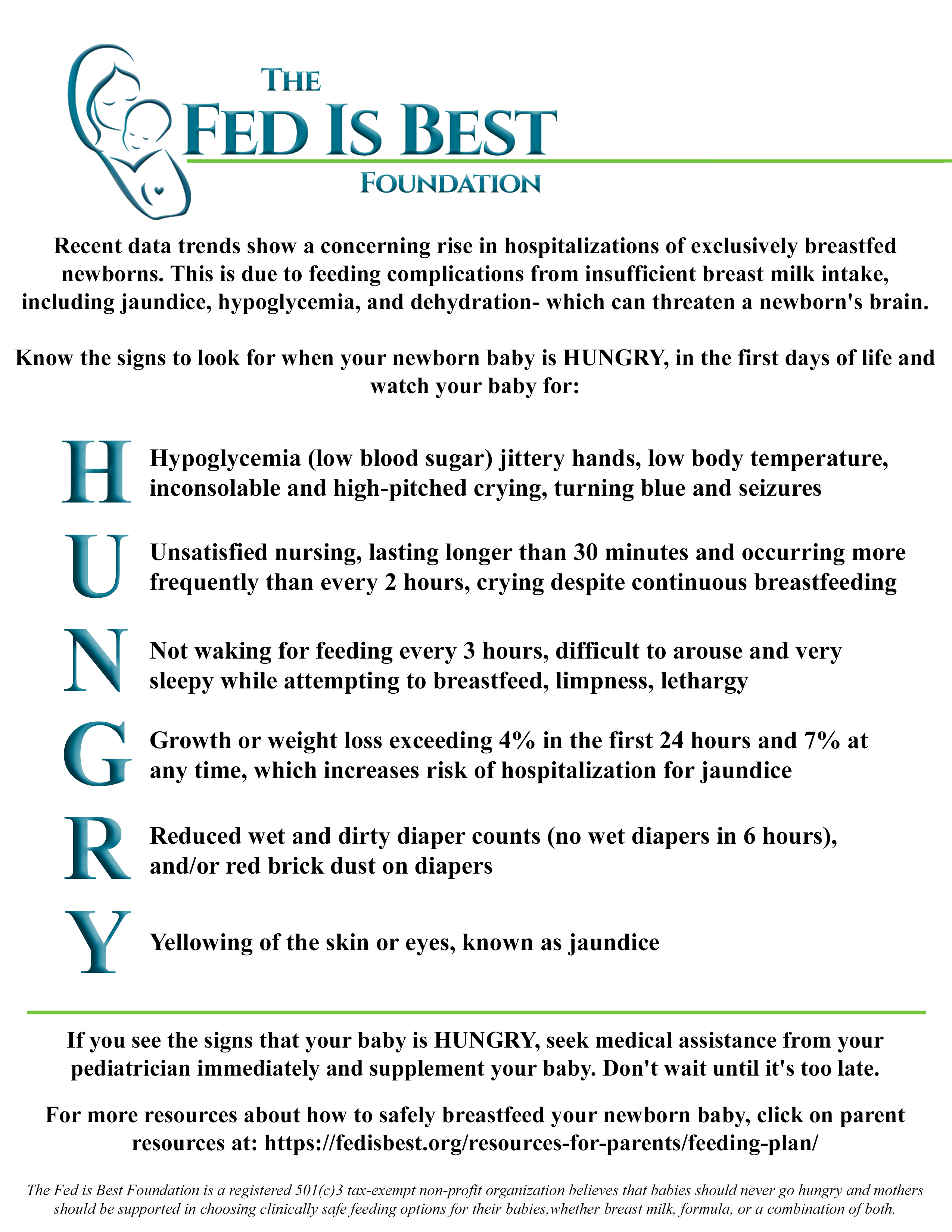

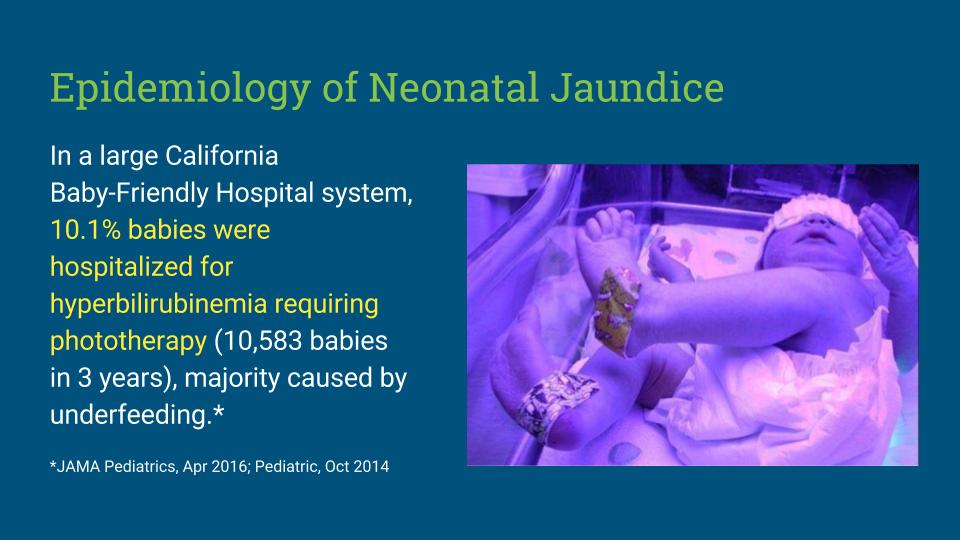

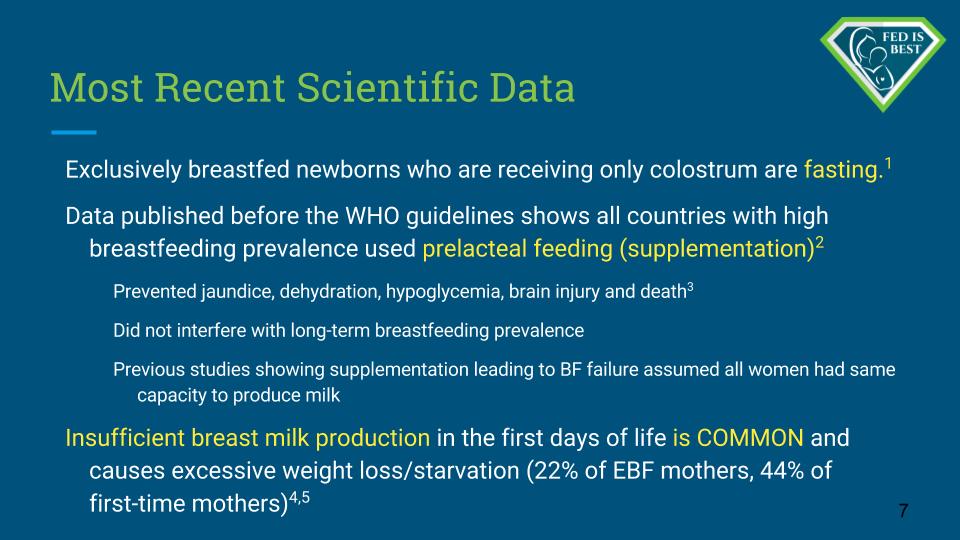

Due to her early term status and her bruise, we were told she was at risk for jaundice. (hyperbilirubinemia) While they told us that they would be watching her bilirubin levels closely, and were encouraged to attend the hospital’s breastfeeding class, we were allowed and encouraged to continue with our original plan of exclusive nursing. Despite my high level of breastfeeding education, I had never learned about this condition, and I didn’t know that it can be greatly exacerbated or triggered by dehydration. I had never been educated on starvation related complications, and only knew that occasionally some babies lost too much weight due to milk supply problems. I had heard of jaundice, but everything I had read indicated that it was “common” in breastfed babies and nothing to worry about in most cases. Regardless, my great care team didn’t seem to be concerned enough to recommend a change in feeding plan, so we just continued with our original plans as if she was like any other baby.

We attended a one on one breastfeeding class with a RN IBCLC, who reviewed my daughter’s latch and confirmed the presence of colostrum on my nipples. Given that the baby was still less than 24 hours old and we were doing pretty well with nursing, the consultant didn’t see anything wrong or of concern. But before we were discharged the following day, my daughter’s discharging physician told us that he wanted her to be seen by our pediatrician the next morning, less than 24 hours after discharge, just in case. Her bilirubin screen had come back elevated at 9mg/dl, and while he wasn’t too concerned, he wanted to make sure we didn’t go longer than 24 hours without someone checking us. At the time I didn’t realize just how critical this advice would be and figured it was just a precaution. With that, we left home with our brand new baby.

That night, I had officially surpassed 48 hours postpartum but I still hadn’t experienced any engorgement. The baby was still nursing on demand, but as the night wore on we seemed to be having more difficulty, not less. This didn’t make sense to me – didn’t all the manuals say that by and large babies get BETTER at nursing over time? And where was that engorgement I was supposed to be experiencing? But we kept trying, nursing on demand or at least every 2 hours whichever came first, and patiently relatching her over and over as she would drift off lazily. She seemed to be forgetting how to latch and was becoming more disorganized – latching weakly, popping off, falling asleep after only a few minutes. We tried all the tricks to keep her awake but it was clear this baby just wasn’t having it.

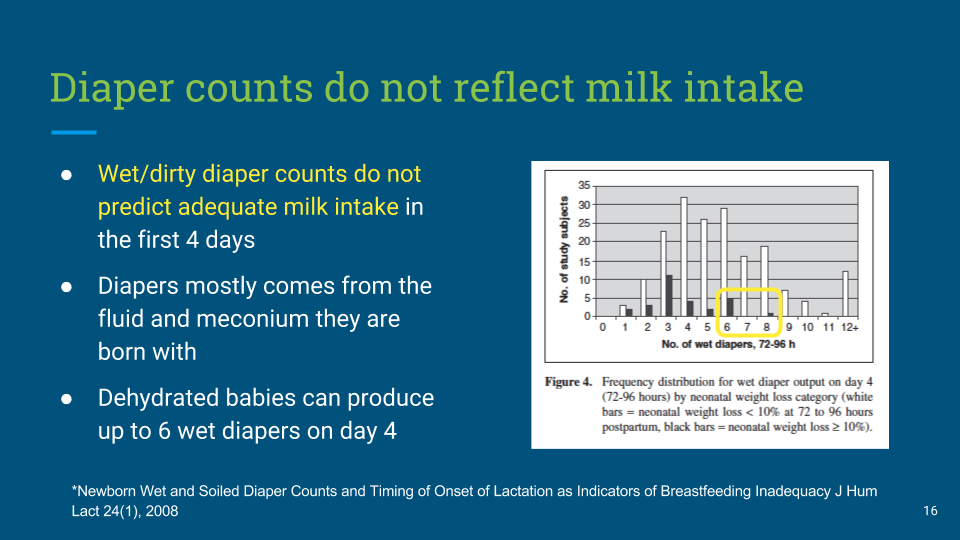

By the wee hours of the morning, I was the one waking her up to eat, not the other way around. In frustration I referred back to all of my breastfeeding resources, but they all clearly reiterated that nursing on demand was best, and that bottles and supplementation were to be avoided. They assured me jaundice was common in breastfed babies and that newborns were frequently “sleepy” at the breast. Instinctively I felt something wasn’t right, but she continued to meet the minimum required wet/poopy diapers so I doubted myself. I stuck to my intellectual rationalizations, and reliance on my breastfeeding training and guidelines won out over new mama instinct. I was not going to be one of those “anxious” and “uneducated” moms who got nervous and supplemented their baby – no, I was going to do this thing RIGHT despite my growing unease. I was armed with my breastfeeding education, my knowledge of the AAP and WHO guidelines, and an iron will.

By the wee hours of the morning, I was the one waking her up to eat, not the other way around. In frustration I referred back to all of my breastfeeding resources, but they all clearly reiterated that nursing on demand was best, and that bottles and supplementation were to be avoided. They assured me jaundice was common in breastfed babies and that newborns were frequently “sleepy” at the breast. Instinctively I felt something wasn’t right, but she continued to meet the minimum required wet/poopy diapers so I doubted myself. I stuck to my intellectual rationalizations, and reliance on my breastfeeding training and guidelines won out over new mama instinct. I was not going to be one of those “anxious” and “uneducated” moms who got nervous and supplemented their baby – no, I was going to do this thing RIGHT despite my growing unease. I was armed with my breastfeeding education, my knowledge of the AAP and WHO guidelines, and an iron will.

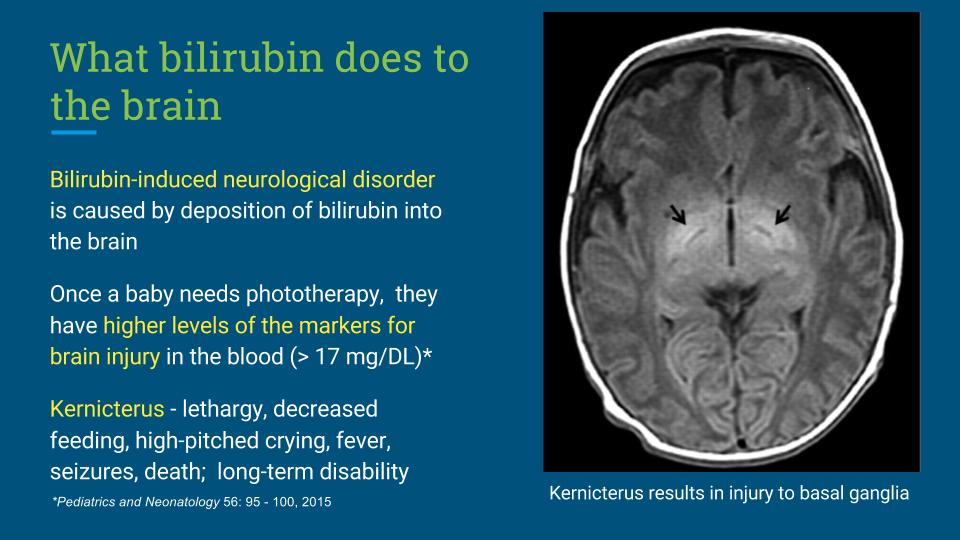

The next morning we bundled our now very yellow baby up to go off to her appointment. Our appointment was at 9am, only 20 hours after we were discharged. First we ran to the lab for a bilirubin stick, and then up to the office for our appointment. The NP walked in, took one look at our little girl, and immediately sat us down and tried to get her to nurse. Within a few moments she confirmed the baby wasn’t eating appropriately and was definitely dehydrated. Eventually we were able to get her to latch with a nipple shield, which was a great relief but it was clear she was still struggling. So we sat there in the office and tried to nurse as we waited for the lab results. When they came back, the NP came back in and kindly told us that we needed to go to the hospital immediately. Our daughter was dehydrated and her bilirubin was 20.7mg/dl. No, we couldn’t even drive home and pack an overnight bag – we had to go. RIGHT NOW. They were even calling the hospital ahead of our arrival, so a room and phototherapy bassinet would be ready and waiting when we got there.

It’s funny – when I was in unmedicated labor, I didn’t cry. Even when I was stuck pushing for hours in agony with a baby who refused to come out, I didn’t cry. But I cried when they told me my brand new baby was starving in my arms, despite my best efforts, despite the fact that I had done everything exactly right.

At the hospital, a wonderful pediatric nurse greeted us and quickly debriefed us on hyperbilirubinemia treatment. Our daughter had to eat something, right away and then she would spend the next day or so under the phototherapy lights. The nurse cautiously approached me with a bottle of formula, gently asking if it was okay if she fed the baby some, given her condition. Thinking back, I must have looked shocked and unpredictable, like a deer in headlights. No doubt this clinician thought I might actually be crazy enough to refuse the formula. I might be so disoriented and obsessed with breastfeeding that I might actually make my baby wait an additional half hour to see what I could pump before giving her something to eat. But thankfully, I heard myself eagerly agree, and felt comfort seeing my husband also nodding vigorously as well. He was scared too. My poor girl sucked down that bottle like lightening. In that moment, my fears from the night before were confirmed.

She had been slowly starving. The exclusivity guidelines had been WRONG.

From then on out, I pumped every two hours and my husband and I took turns taking the baby out from the lights, changing her, feeding her, and then immediately returning her to her phototherapy bassinet. During my second pumping session, the nurse came in and noticed the meager milliliters of colostrum/milk I had produced and confirmed that milk had not arrived yet.

I was 72 hours postpartum, and was barely producing a half ounce total. Later I would discover that this is not normal. With rigorous 2hr pumping, my milk finally arrived the following evening…about 4.5 days after giving birth. But even with its arrival, it was still not enough and we had to top up with formula. The next morning my daughter’s bilirubin had dropped back down to a safe level and we were discharged home with instructions to triple feed – attempt to nurse, bottle feed with milk and formula, and then pump.

The clinical team determined her condition had been caused by her existing physiologic vulnerability, combined with ineffective feeding, lack of intake, and subsequent dehydration. A dangerous mix.

I wish I could say that we overcame the rough start and went on to breastfeed exclusively. After all, aren’t we taught that with enough grit and determination we can do anything? Aren’t we told, from the moment we conceive, that breastfeeding is all about how much you know, how hard you try, and how much support you have? I had immense amounts of all three, so I just knew we were going to succeed in achieving that breastfeeding holy grail – exclusivity. I just had to sacrifice, and I was ready and willing.

I was religious about my pumping and painstakingly recorded my outputs along with exactly how much my daughter was eating, and the ratio of breastmilk to formula she was receiving at each feed. And of course, we were nursing too. After a rough first start, our nursing seemed to improve a little bit over time and I was anxious to get the all clear to start nursing without pumping. A week later, we visited our pediatrician’s office LC and she diligently helped me latch the baby, and conducted a weighted feed. After 20 minutes of nursing, we were both feeling hopeful. We knew I had milk (even if it wasn’t necessarily enough to fully feed her just yet) and we had watched her latch and nurse for an extended period. So you can imagine our dismay when the weighted feed indicated that my daughter, a baby who was happily taking 1.5-2oz per bottle feed, hadn’t even extracted half an ounce. What appeared to be a sleepy baby popping off the breast was actually a fatigued infant who just couldn’t work at it anymore, despite not having received sufficient nutrition. My beautiful baby girl, despite her best efforts, was an ineffective nurser. Later I would learn that this is not an uncommon scenario for early term infants, but at the time it felt like it was my fault. The LC reassured me we would keep trying, but told me that it was not safe to go back to exclusive nursing just yet. If I wanted to breastfeed, I had to keep pumping, as the baby was not nursing effectively to keep my supply going. And if I wanted to keep the baby well fed, I also had to keep the formula because I was clearly not pumping enough to meet her needs. And if I wanted to try to salvage nursing, I had to keep practicing that too, because the baby would definitely get so used to the bottle at some point that she might find it hard to go back.

It was triple feeds…indefinitely…until I showed improvement or burned out. So I was sent home with instructions to triple feed, take a bunch of fenugreek, drink lots of water, and eat plenty of calories. Because oh yeah, let’s not forget that I had to work on fixing my supply too.

Every week I called my consultant to update her, and each week she patiently and compassionately heard my frustrations and helped me brainstorm new ways to try to battle back from this complete fiasco. I changed my diet to include more fats and calories, started taking GoLacta, and power pumped. I rented a hospital grade pump and endured the “max comfort” level, attempting to squeeze every drop of milk from my body. But my supply never improved and my daughter continued to outpace me. I was always behind, never catching up. By week six, her nursing latch had deteriorated to the point where it was physical and psychological torture trying to get her to nurse. I just didn’t have the fight left in me to insist on keeping up the triple feed schedule for EVERY SINGLE FEEDING. So we focused mostly on pumping, and still practiced nursing a few times a day. My hopes of nursing were fading fast, so I doubled down on my pumping routine. I was an impending failure with nursing, and I refused to be a failure at pumping, even though it was killing me inside. Every time I hooked myself up I hoped I would see a boost in output. And every time, every 2 hours, of every day, when I failed to achieve that increase, I was reminded that I was failing at that too.

By week 10, I realized I couldn’t go on. I had nothing left to give. I had literally been pumped dry – of milk, of willpower, of energy, of positivity and joy. The only thing left to try was prescription medications and I drew the line there. Ten weeks of round the clock breastfeeding obsession had forced me to acknowledge the ugly truth. I was never going to meet those sacred guidelines no matter how much I pumped or how many pills I took.

In sheer desperation, I decided to reduce my pumping schedule from 9-10x per day to 6x over the course of a couple weeks. I hoped that maybe I could keep going on a more reasonable schedule, and that maybe I would be able to continue to provide some milk. My supply plummeted and all hope of sustaining this until that recommended 6 month mark disappeared completely. By the end of week 13, I was dry and we were a formula feeding family all the way. My depression and extreme feelings of failure continued through month 4 as I struggled with accepting my decision while battling the hormonal changes that occur after a woman stops breastfeeding. Rationally I knew that what I had gone through was extremely unusual. My LC and midwife confirmed it, as did family and friends. Intellectually I knew that I was one of those “rare” women for whom exclusive breastfeeding was truly an impossible task. But I still had anxious thoughts and felt guilty all the time. I felt like a terrible mother. I couldn’t bring myself to mix formula in public for fear of people thinking less of me.

But finally, the clouds started lifting. I was getting so much more sleep, and I no longer had to endure feeling like a failure every few hours at feeding time. I eventually found comfort talking to other moms and spending time on formula positive websites and support groups. By six months my daughter was thriving, happy and healthy and I was genuinely happy about my infant feeding decision.

When I tell my story, I inevitably hear praise and admiration for sticking with it so long. And I understand why…it did take a lot of work and commitment to breastfeed with extreme challenges, and in that way, making it to 3 months was a huge accomplishment. But there is a dark side to that accomplishment. What others see as determination, I know was obsession. What they see as motherly sacrifice, I know was self torture and unhealthy. The truth is, I would never recommend what I did to another mother. I would never encourage a mother to go through the same experience. And I never want to go through that ever again with any future children.

As a low supply mom and a public health professional, I wish breastfeeding advocates, public health authorities and clinicians knew one thing: pushing the idea that exclusivity is the “right” and “best” way to breastfeed is extremely damaging to those mothers and babies who do not have easy breastfeeding experiences. Mothers absolutely will run themselves into the ground trying to achieve something that is not possible, and they will follow well meaning but misguided and overgeneralized recommendations to the point of harming their own infants if they are convinced breast is always best. We are so busy trying to force more women into the exclusive breastfeeding checkbox, that we have lost sight of the whole reason we are trying to do that in the first place. If moms and babies are our first priority, does it really make sense to put a subset of us at risk like this? Are a few extra ounces of breast milk really worth the extreme feelings of failure and depression that the quest for exclusivity brings to moms with low supply? Which is more important – that a baby is well fed or exclusively breastfed?

Instead of pushing and bullying women towards exclusivity, we should encourage women to breastfeed to the best of their unique ability, in a way that is best for them and their baby. For many moms, breastfeeding to the best of their ability will include exclusivity, and that is great. But for moms like me, breastfeeding to the best of their ability may always be combination feeding. It may always be nursing with a supplemental nursing system, or exclusive pumping, or only breastfeeding for a few days or a few weeks.

We need to start telling moms the truth: There is no “right” way to breastfeed…there is only your own unique way. We need to tell moms this from the moment they get pregnant to the moment they stop breastfeeding, whether that be at one week, one month, or one year. We need to drive home the point that breastfeeding looks different for every mom and every baby. We need to send them into that delivery room armed with knowledge, and empowered and encouraged to create an infant feeding plan that they enjoy and that keeps their baby safe and healthy from day one. Right now, we are not doing this. We wait until a mom and baby fail to achieve our perfectionistic standards and then try to clean up the mess and salvage what we can from the damage. When we push a rigid understanding of what successful breastfeeding is, we are setting moms up for failure, and risking a subset of infants in the process.

Hillary Kuzdeba, holds her Master’s degree in public health from Boston University. Her professional interests include women’s health, pediatrics, public health research, and quality and safety within the hospital setting. Over the years, Hillary has worked with vulnerable populations including women with HIV, active substance users, and resettled refugees in initiatives aimed at providing social support, access to care, and health behavior education and modification. More recently, she served as the program coordinator for a growing clinical research group in a pediatric hospital where she managed a high volume of research and quality improvement projects designed to measure and improve patient outcomes in critically ill children. In this role she implemented projects that focused on monitoring infant feeding protocols and plans, and sat on a standing committee of hospital staff and researchers tasked with facilitating the measurement of quality of care across the organization. Hillary supports and is an advisor at the Fed is Best Foundation because she is a mother who experienced breastfeeding difficulties and the emergency readmission of her newborn daughter for hyperbilirubinemia and dehydration. As a professional trained in both health promotion initiatives and quality improvement, she believes that the current exclusive breastfeeding protocols and advice utilized in many hospitals, and promoted by breastfeeding advocacy groups, are directly contributing to the clinical deterioration of a subset of exclusively breastfed infants. Hillary suspects that the Fed is Best approach to breastfeeding, which emphasizes baby’s safety, mother’s well-being, and an inclusive vision of successful breastfeeding, will soon be at the forefront of the ongoing public health conversation on breastfeeding, neonatal health, and postpartum care.

Hillary Kuzdeba, holds her Master’s degree in public health from Boston University. Her professional interests include women’s health, pediatrics, public health research, and quality and safety within the hospital setting. Over the years, Hillary has worked with vulnerable populations including women with HIV, active substance users, and resettled refugees in initiatives aimed at providing social support, access to care, and health behavior education and modification. More recently, she served as the program coordinator for a growing clinical research group in a pediatric hospital where she managed a high volume of research and quality improvement projects designed to measure and improve patient outcomes in critically ill children. In this role she implemented projects that focused on monitoring infant feeding protocols and plans, and sat on a standing committee of hospital staff and researchers tasked with facilitating the measurement of quality of care across the organization. Hillary supports and is an advisor at the Fed is Best Foundation because she is a mother who experienced breastfeeding difficulties and the emergency readmission of her newborn daughter for hyperbilirubinemia and dehydration. As a professional trained in both health promotion initiatives and quality improvement, she believes that the current exclusive breastfeeding protocols and advice utilized in many hospitals, and promoted by breastfeeding advocacy groups, are directly contributing to the clinical deterioration of a subset of exclusively breastfed infants. Hillary suspects that the Fed is Best approach to breastfeeding, which emphasizes baby’s safety, mother’s well-being, and an inclusive vision of successful breastfeeding, will soon be at the forefront of the ongoing public health conversation on breastfeeding, neonatal health, and postpartum care.

To join our world wide Fed Is Best Foundation Team: contact@fedisbest.org

For resources to safely breastfeed your baby : https://fedisbest.org/resources-for-parents/feeding-plan/

To donate to our non-profit Foundation : https://fedisbest.org/donate/

I just read your article today as I sit here weaning from BF myself. My story is essentially identical to yours. Baby was only transferring 1/2 oz at a time. Additionally I ended up with a blood clot lodged in my left lung shortly after delivery (a consequence of a rapid delivery). I had been so hypertensive after delivery due to the clot that my milk never came in properly. Baby was being supplemented from very early on and I just KNEW that if I pumped more often (I could spend HOURS a day pumping to see an increase in output), tried harder, worked at it better – that I could get back to exclusivity. It was when I was seriously considering ordering illegal drugs from a Canadian pharmacy that I knew it was time to give it up.

So much pressure and I’ll never get that time back. Fed is best and my daughter will be better off for it. Even if it stings now that I “failed” – all I care about is seeing her thrive.

Thank you for this! I’m in the same boat right now at 10 weeks (although I had the worst LC experience in the world where they threatened to call child protective services on me when I eventually decided to follow my pediatrician’s advice and supplement instead of pumping the FIVE HOURS A DAY that the LC recommended… literally!), and it’s so good to hear I’m not alone! Thank you!

My story mirrors yours and thank you for sharing. I made it a week and a half pumping only getting 2-4 mL at a time. Yes my milk was in and no amount of pumping would have helped. I pumped from day 1 and hand expressed. We supplemented from day 2 as I knew the tiny amount of colostrum wasn’t enough. Triple feeds were killing me as I got no sleep. We made decision to go with formula and I feel like a new mother. Thanks for support.

Your experience at nursing reads as though it were mine. For years I have endured guilt that “I” wasn’t more successful, despite the fact that I was pumping round the clock to produce at best 4 oz. Eventually, I had to admit that my child was going to formula fed …with breastmilk as a very meager supplement. Compounding that guilt was the fact that later in life when he developed asthma and was diagnosed with a peanut allergy, there were people around me who blamed this on my not having exclusively breastfed. I live in a city where “Breast is Best” has the fervor of a religious mantra. I have seen many mothers struggle and be criticized for having trouble.

So you were brave enough to not listen to them about the cps thing? I was turned into cps while in hospital because I wanted my baby in the nursery….I had minor surgery after his birth and wanted the rest…staff said I was rejecting him

I’m in the midst of all this right now…I didn’t have an unusual birth or anything that would warrant low supply. At her first doctors appointment, she had lost enough that they wanted me to start supplementing with formula. We are now six weeks in and triple feeding every day. Nursing, bottle feeding, then pumping. The most I ever pump is a combined 3 ounces in the middle of the night. Most of the time I squeak out an ounce every 2 hours. We finally bought a scale so we could do weighted feedings at home, and after what looks like a very successful nursing session… she’s barely taken an ounce. So essentially, my baby is burning more calories trying to nurse then she’s probably taking in. I’ve committed to two more weeks, but only because I put my baby through the trauma of a tongue tie revision when she was 4 weeks, and I feel guilty not continuing to try. It’s extra heart breaking because my girl LOVES nursing. She will look for my breasts even after she has filled up on a bottle. I’m making my peace with it, but I truly regret making her go through the tongue tie procedure. Live and learn I guess…it’ll probably be a relief when I can just nurse her for comfort. Thinking I’ll pump every 3-4 hours just so she can have the benefit of a couple breast milk bottles a day…at least til the pumps run totally dry. Thank you for your post. I feel like we really do women a disservice by flooding social media with photos of freezers full of milk and stories about magic lactation cookies. I literally did all the things…the lactation nurse told me I was her most dedicated patient. All to no avail. I wish I could have back the hours spent worrying and scouring the internet for fixes.