by Christie del Castillo-Hegyi, M.D.

One of the most important duties of the medical profession is to make health recommendations to the public based on verifiable and solid evidence that their recommendations are safe and improve the health of nearly every patient, most especially if the recommendations apply to vulnerable newborns. In order to do this, major health recommendations require extensive research regarding the safety of the real-life application of the recommendation at the minimum.

Multiple health organizations recommend exclusive breastfeeding from birth to 6 months as the ideal form of feeding for all babies under the belief that all but a rare mother can exclusively breastfeed during that time frame without underfeeding or causing fasting or starvation physiology in their baby. In order to suggest that exclusive breastfeeding is ideal for all, if not the majority of babies, one would expect the health organizations to have researched and confirmed that all but a rare mother in fact produce sufficient milk to meet the caloric and fluid requirements of the babies every single day of the 6 months without causing harmful fasting conditions or starvation. There have been few studies on the true daily production of breast milk in breastfeeding mothers. Only two small studies quantified the daily production of exclusively breastfeeding mothers including a study published in 1984, which measured the milk production of 9 mothers, and one in 1988, which measured it in 12 mothers. After extensive review of the scientific literature, it appears the evidence that it is rare for a mother to to not be able to produce enough breast milk to exclusively breastfeed for 6 months is no where to be found. In fact the scientific literature has found quite the opposite.

In November 2016, the largest quantitative study of breast milk production in the first 4 week after birth of term infants was published in the journal Nutrients by human milk scientists, Dr. Jacqueline Kent, Dr. Hazel Gardner and Dr. Donna Geddes from the University of Western Australia. They recruited a convenience sample of 116 breastfeeding mothers with and without breastfeeding problems who agreed to do 24 hour milk measurements through weighed and pumped feedings between days 6 and 28 after birth and were loaned accurate clinical-grade digital scales to measure their milk production at home. The participants test weighed their own infants before and after breastfeeding or supplementary feeds and recorded the amounts of breast milk expressed (1 mL = 1 gram). All breast milk transferred to the baby, all breast milk expressed and all supplementary volumes were recorded as well as the duration of each feed.

These were the results…

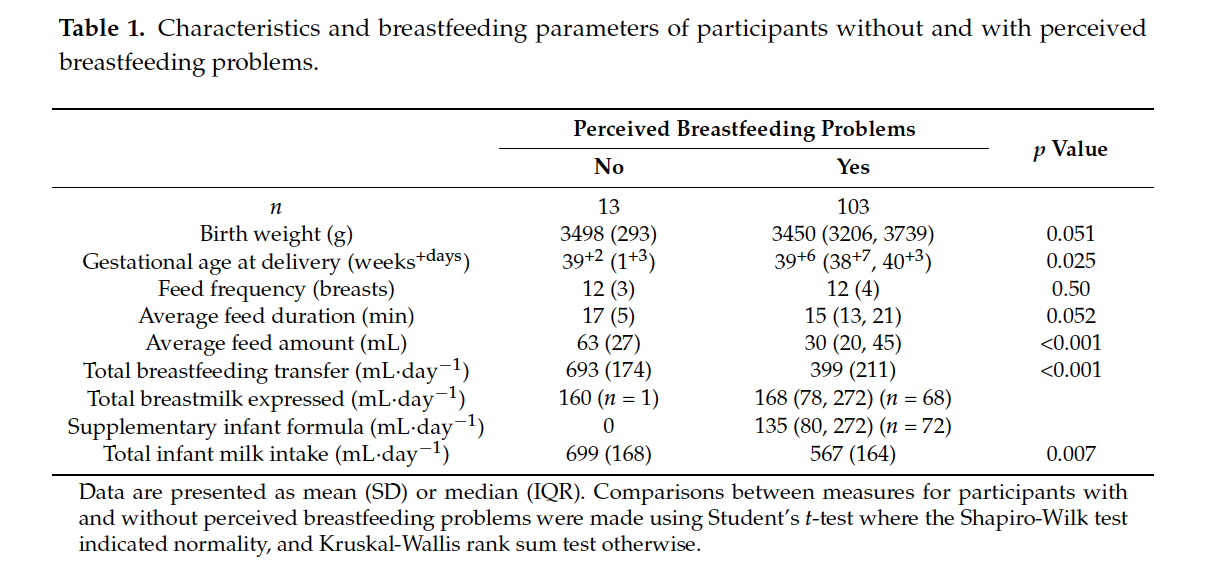

13 mothers perceived no breastfeeding problems while 103 mothers perceived breastfeeding problems. The most common problem was insufficient milk supply (59 mothers) followed by pain (11 mothers), and positioning/attachment (10 participants). 75 mothers with reported breastfeeding problems were supplementing with expressed breast milk and/or infant formula.

Of the mothers with reported breastfeeding problems, their average weighed feeding volumes were statistically lower than the mothers who did not report breastfeeding problems with an average feed volume of 30 mL vs. 63 mL in the mothers who reported no breastfeeding problems (p<0.001). The daily total volume of breast milk they were able to transfer (or feed directly through breastfeeding) were also statistically lower than those who did not report breastfeeding problems. The moms without breastfeeding problems transferred an average of 693 mL/day while those that reported breastfeeding problems transferred an average of 399 mL/day (p<0.001). The study defined 440 mL of breast milk a day as the minimum required to safely exclusively breastfeed. This is the amount of breast milk that, on average, would be just enough to meet the daily caloric requirement of a 3 kg newborn (at 70 Cal/dL and 100 Cal/kg/day). Babies of mothers with no reported breastfeeding problems were statistically fed more milk than those with breastfeeding problems, 699 mL vs. 567 mL per day (p = 0.007). All 13 mothers who perceived no breastfeeding problems produced and transferred more than the study’s 440 mL cut-off as the volume required to be able to exclusively breastfeed. What this data shows is that a mother’s perception of breastfeeding problems is associated with actual insufficient volume of breast milk fed to her child.

Based on the 440 mL cut-off for “sufficient” breast milk production, some mothers who report their babies not getting enough in fact produced more than 440 mL. However, since 440 mL is the amount of milk that is needed to meet the minimum caloric requirement of a 3 kg newborn, if the mother had a newborn weighing > 3 kg as they would expect to be past the first days of life if growing appropriately, many of the mothers reporting breastfeeding problems may be producing more than 440 mL but are still in fact producing less than the amount to keep their child satisfied and fed enough to grow. A supply of 440 mL would actually be just enough milk to cause a 3 kg newborn to be diagnosed to fail to thrive at 1 month since they would not gain any weight if fed this volume of milk. Failure to thrive has known long-term consequences including lower IQ at 8 years of age. So their conclusion that some mother’s perception of insufficient breast milk may in fact be inaccurate as a volume of 440 mL is in fact “not enough” for most newborns weighing > 3 kg.

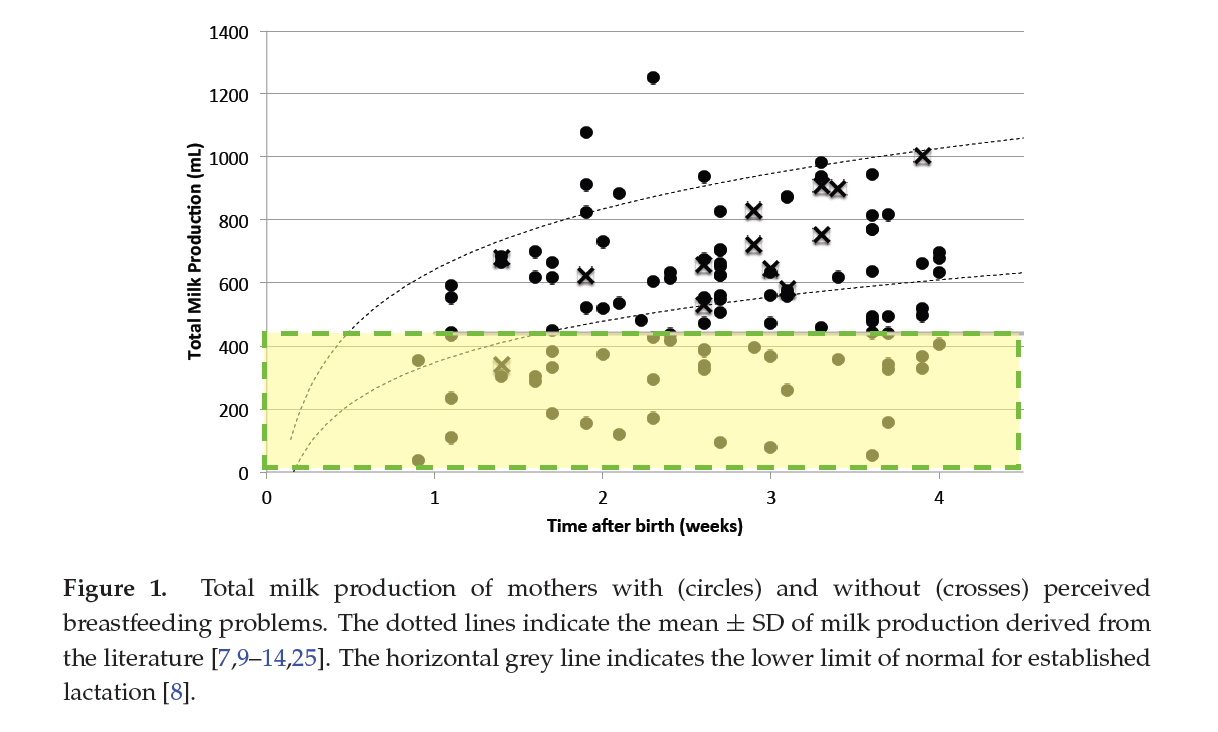

The figure below shows the daily production of breast milk by breastfeeding mothers over the 4 week course. The crosses showed the total breast milk production of mothers without reported breastfeeding problems and the dots reflected the mothers with reported breastfeeding problems. Unfortunately, the figure did not distinguish whether the reported problems were due to poor positioning and attachment or pain while breastfeeding versus breast milk supply. The study found that 2/3rd of mothers in this study did not produce the minimum milk 440 mL they defined to exclusively breastfeed safely between days 11 and 13 of life. Between days 14 and 28 of life, 1/3rd of mothers did not produce the minimum 440 mL. While the study population were disproportionately made up of mothers who reported breastfeeding problems, the study suggests that there is actual association between “perceived” breastfeeding problems and actual problems with milk supply.

As it stands, the number of women who report breastfeeding problems due to insufficient milk supply is much larger than what mothers are taught through their breastfeeding education sources. According to a review of the peer-reviewed literature by Human Milk Scientist Dr. Shannon Kelleher, Ph.D., the number of mothers who have insufficient breast milk supply may be much larger that what is commonly taught. Currently, it is the most common reason reported by mothers who do not exclusively breastfeed for the first 6 months of life. The Infant Feeding Practices Study II (IFPS II) was drawn from 500,000 households in the United States. Approximately 4,900 pregnant women ages 18 and above participated, and of those, 2,000 received questionnaires throughout the first year of their infant’s life between May 2005-2006 (Li et al, Pediatrics 2008).

- Although 75% of new mothers intend to breastfeed, not all women are able to breastfeed their infants exclusively for the first 6 months of life, as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the World Health Organization;

- It is estimated that the prevalence of women who overtly fail to produce enough milk may be as high as 10–15% and can quickly lead to hypernatremia (high blood sodium levels) nutritional deficiencies, or failure to thrive;

- The prevalence of lactation “insufficiency” may be much higher, as 40–50% of women in the US and 60–90% of women internationally cite “not producing enough milk” or that their baby was “not satisfied with breast milk” as the primary reasons for weaning prior to 6 months.

It is therefore important to do objective measurements of breast milk supply through 24 hour diaries of test weighing as well as supplemented and pumped breast milk volumes as well as routine weighing of breastfed babies to prevent newborn starvation and failure to thrive. A mother showing concerns that her child is not receiving enough should receive more than reassurance and encouragement and should receive objective testing to measure her child’s actual daily intake and daily growth in order to protect the brain and vital organs.

Discussion

What this means is if a mother says her breast milk supply is not enough, she is likely correct. She may be able to get additional milk through pumping but for many mothers in the first month of life, supplementation will likely be necessary to keep her child from going hungry and experiencing fasting conditions. Babies who receive too little milk can experience starvation-related complications including injury to the brain and vital organs. If you are a breastfeeding mother who is worried about your child not getting enough though breastfeeding, both your baby and your breastfeeding need evaluation by a pediatrician and a qualified breastfeeding professional.

Because of the belief that need for supplementation is rare, breastfeeding advocacy organizations as recently as this month have restated their recommendation that health professionals should aim to avoid supplementation unless a child is experiencing true metabolic complications associated with underfeeding and starvation as defined by their supplementation guidelines. It is not sufficient for a child to be showing obvious signs of hunger like crying or hours of nursing to be offered supplementation while they are losing weight and receiving a fraction of their caloric and fluid requirement.

The studies typically included few mothers and others did not actually quantify the volume of milk produced and actually fed (or transferred) to the baby. The remaining studies on breast milk sufficiency only reported on “perceived” milk insufficiency, which much of the literature dismisses are related to poor confidence, misinterpretation of baby’s crying and are largely viewed as inaccurate and not an actual measure of true milk sufficiency.

There are many ways you can support the mission of the Fed is Best Foundation. Please consider contributing in the following ways:

- Join the Fed is Best Volunteer group to help us reach Obstetric Health Providers to advocate for counseling of new mothers on the importance of safe infant feeding.

- Make a donation to the Fed is Best Foundation. We are using funds from donations to cover the cost of our website, our social media ads, our printing and mailing costs to reach health providers and hospitals. We do not accept donations from breast- or formula-feeding companies and 100% of your donations go toward these operational costs. All the work of the Foundation is achieved via the pro bono and volunteer work of its supporters.

- Share the stories and the message of the Fed is Best Foundation through word-of-mouth, by posting on your social media page and by sending our resources to expectant moms that you know. Share the Fed is Best campaign letter with everyone you know.

- Write a letter to your health providers and hospitals about the Fed is Best Foundation. Write them about feeding complications your child may have experienced.

- Print out our letter to obstetric providers and mail them to your local obstetricians, midwives, family practitioners who provide obstetric care and hospitals.

- Write your local elected officials about what is happening to newborn babies in hospitals and ask for legal protection of newborn babies from underfeeding and of mother’s rights to honest informed consent on the risks of insufficient feeding of breastfed babies.

- Send us your stories. Share with us your successes, your struggles and every thing in between. Every story saves another child from experiencing the same and teaches another mom how to safely feed her baby. Every voice contributes to change.

Send us messages of support. We work every single day to make infant feeding safe and supportive of every mother and child. Your messages of support keep us all going.

One thought on “Breast Milk Production in the First Month after Birth of Term Infants”