I wish I had done more research about hospital exclusive breastfeeding policies before my son was born. I’m a registered nurse with a Bachelor of Science in Nursing, but my maternity and pediatric experience was limited to nursing school. I was always on the fence about breastfeeding—I said that it was my goal but that we would see, so I hadn’t bought in to the narrative of “Breast is Best”. Still, I expected the medical professionals at the hospital where my son was born to tell me if they thought my baby was starving while attempting to exclusively breastfeed.

I delivered at the University of North Carolina Hospital, a top medical center. I felt reassured that I was in great hands. They were called “baby friendly” after all. I didn’t look into what that meant, and I thought I was well prepared. I was induced after being diagnosed with preeclampsia, but, thankfully, it was caught very early. I was two days shy of forty weeks. I had a long labor, followed by a C-section due to my son’s position. I’m also thirty-five years old, so by all accounts, I was high risk. It also meant I was at risk for late or low breast milk supply.

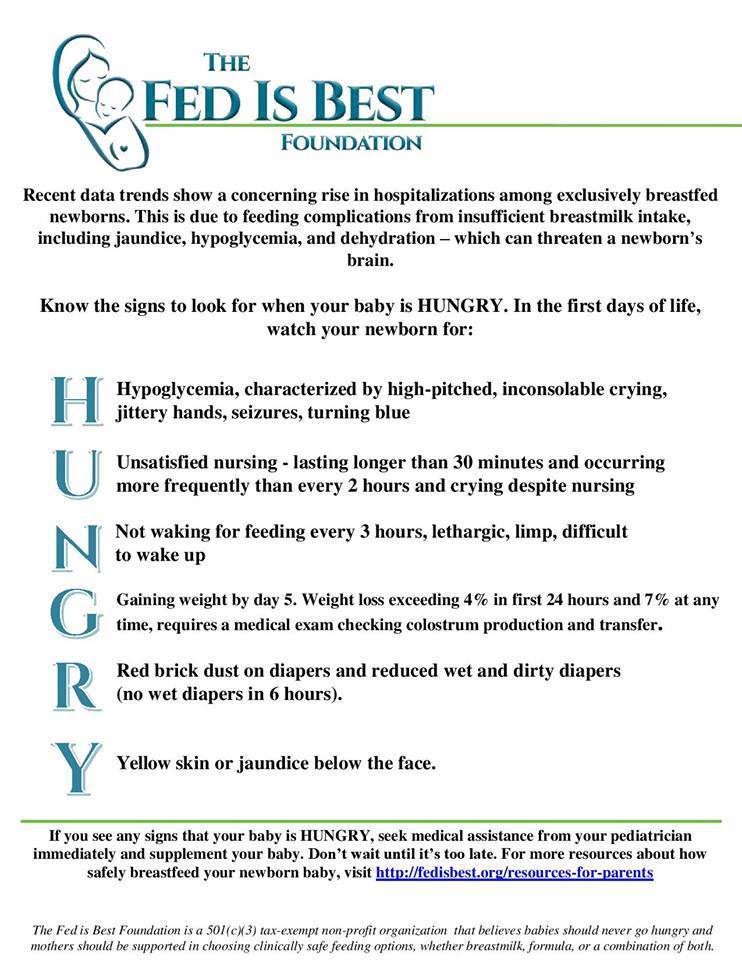

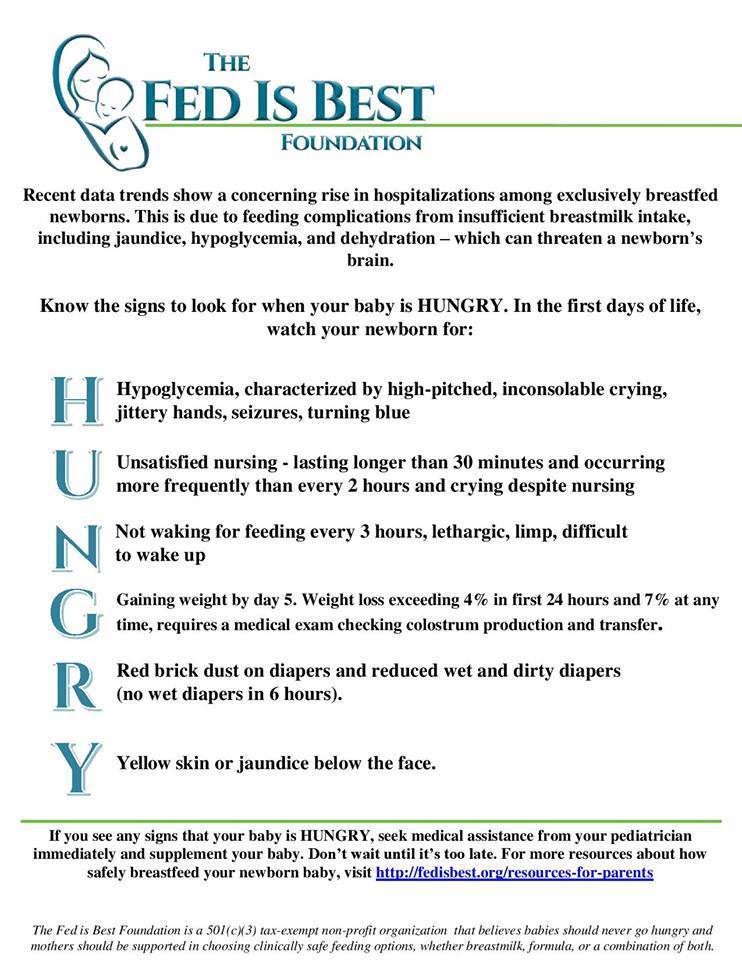

First, my husband and I were laughed at when we said we planned to use the nursery. Thank God for my husband—he did the baby care and brought our son to me while I was bedridden so that I could breastfeed. I was told the latch was great. I felt confident things were going well. But my son was inconsolable by the time he was forty-eight hours old.

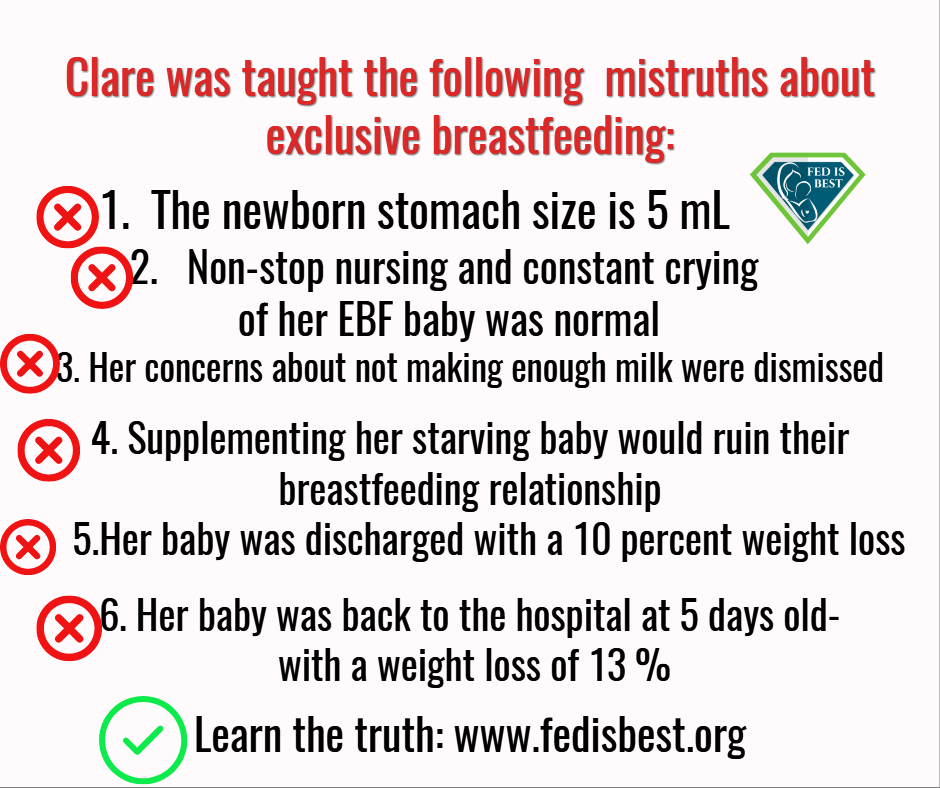

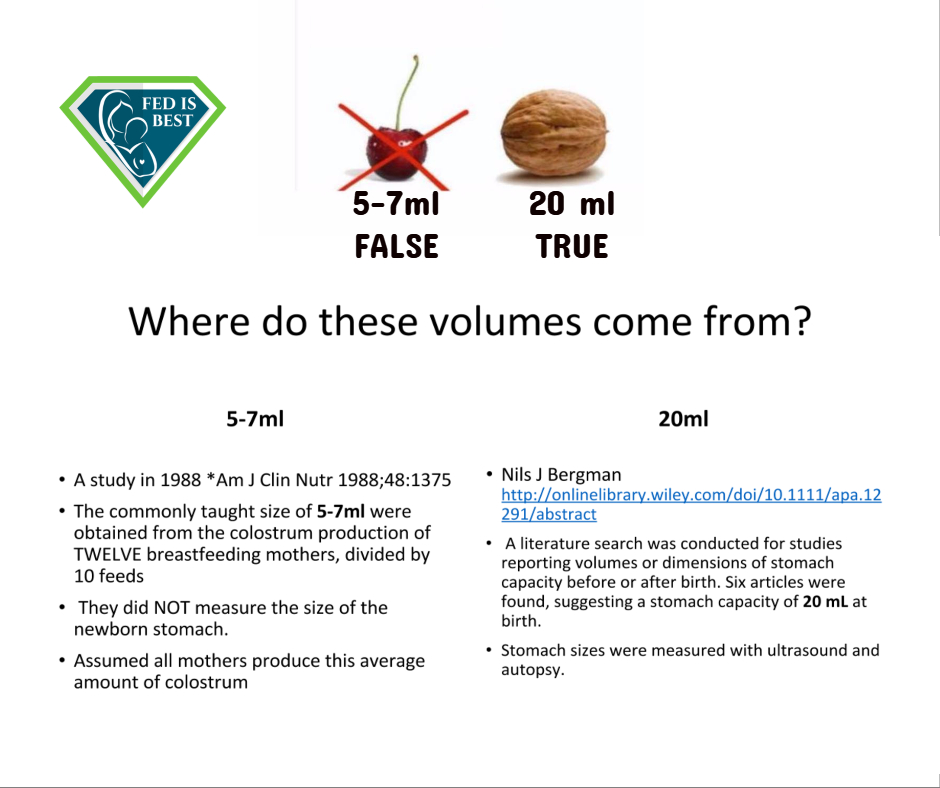

My baby nursed a lot. I was told everything was normal and he was “cluster feeding”. Later, as my training came back to me, I never remembered cluster feeding being a thing. During my training, babies were supplemented when mothers didn’t have enough colostrum babies were supplemented and were taken to the nursery if a parent requested. I went to Duke University, and I rotated through WakeMed. These are excellent hospital systems.

I was concerned about my baby’s very dry lips, and I was told not to worry. I asked about the few wet diapers that my son produced. Dismissed. I trusted that the medical professionals had my and my baby’s best interests at heart. I asked if maybe my milk hadn’t come in, and I was told all is well. We went home on the evening of the third day after birth, and my baby was looking jaundiced. He cried a lot, but nursing helped soothe him from crying–sometimes.

We saw the pediatrician the next day, and I found out my son had lost twelve percent of his weight since birth. We did a weighted feed in the doctor’s office, and his weight before and after nursing were exactly the same. My pediatrician, my husband, and I had a conversation about giving the baby formula. My husband and I had already decided we were going to supplement with formula before we saw the pediatrician, and our son’s weight loss confirmed that we were right to do so. We did not hesitate, and he had his first bottle minutes after we got home. He sucked it down, and he was finally calm and content for the first time in days. I tried to pump and barely got anything. My milk eventually came in, but we continue to supplement. His weight rebounded, and he gained well, but I was beside myself knowing that my baby had starved. It shouldn’t have come to that.

I am upset that the nurses (most of whom were fairly new) don’t know the difference between true cluster feeding and starvation. I am livid that no one even suggested formula.

Continue reading →