By C. Faust

As a neonatal nurse practitioner in a community hospital, I see babies in the postpartum unit every day and make decisions about their discharge criteria.

The average length of stay after birth is 24-48 hours for a vaginal delivery and 48-72 hours for cesarean delivery. A lot of information about breastfeeding, newborn care, and post-partum care must be conveyed in that short time, often to new parents who are exhausted and overwhelmed. In an ideal world, every mother-baby dyad would be well suited for breastfeeding. Many women are able to breastfeed without difficulty, but for some, it’s a struggle. The majority of mothers are discharged before their milk comes in, which is why discharge criteria include pediatrician follow-up within 24-48 hours and why weight check appointments are critical so that all breastfeeding babies are protected from inadequate milk intake.

“Days two to five are critical days for normal newborns to be seen by their pediatrician,” said Dr. Vicki Roe, M.D., a pediatrician at North Point Pediatrics in Indiana. “They are still losing weight and their jaundice levels could be increasing. A healthy baby can become a very sick baby quickly, and we must monitor them closely to prevent complications.”

Many of us work in “Baby Friendly” hospitals. Requirements for the Baby-Friendly designation include displaying the WHO/Unicef Ten Steps for successful breastfeeding and adhering to these recommendations. It is important to note that Baby-Friendly does not prohibit supplemental feeding in the case of medical necessity; nevertheless, both medical staff and nursing staff often report that they are afraid to violate the Baby-Friendly “rules.” I find it effective to specifically document the condition I am treating when I order supplemental feedings. This makes the plan of care transparent and easy to communicate, ensures accountability, and meets the requirements of certification. The exclusively breastfed baby with excessive weight loss (EWL) requires careful assessment.

Question: Would you consider laboratory testing if a baby has excessive weight loss and the mother’s milk is not in yet to meet discharge criteria?

A weight loss of 7-10 % certainly prompts further feeding evaluation. A physical exam should be performed, looking for clinical signs of dehydration. I would consider ordering a Basal Metabolic Panel (BMP) to evaluate for dehydration, hypernatremia, and hypoglycemia. In some situations, the decision to supplement based on excessive weight loss may be met with pushback; laboratory evidence of dehydration adds weight to the decision and may forestall disagreement. In our facility, we usually do bilirubin (jaundice) screening using a transcutaneous meter at around 24 hours of life; if I were concerned about weight loss, particularly if there were visible jaundice or risk factors, I would repeat the screening. And of course, if the infant’s clinical appearance were of concern, for instance, if the infant were hypotonic or lethargic, a CBC or complete blood count and blood culture would be of paramount importance to check for infection.

Question: Do you take into consideration the mothers’ risk factors for delayed onset of milk when considering supplementation?

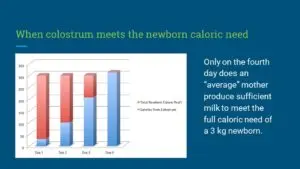

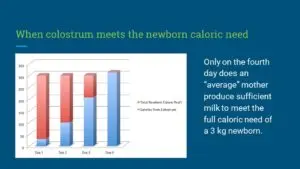

Absolutely. The considerations I have outlined below are drivers in assessing not only readiness for discharge but also whether there is an indication for supplementation. A healthy infant born at term and appropriate size for gestational age with no complications can endure a couple of days of low volume colostrum feedings while mother’s milk is coming in. I use the analogy of a bear storing up for hibernation when I speak to parents about prenatal stores and normal expectations for breastfeeding. Maternal considerations and infant health status inform the decision of whether supplemental feeding is needed. A lactation consultant may be of assistance if lactogenesis is delayed and can implement interventions such as pumping or adjusting the infant’s latch and positioning. It is important to work as a team; LCs can offer valuable input into the plan of care, but they can’t make decisions without consulting with the pediatrician. When a medical need for supplemental feeding is recognized, an appropriate plan of care must accurately be conveyed and followed by everyone involved in the care of the dyad.

Question: If a mother has IV fluids during labor, do you think babies who have excessive weight loss can lose more weight than the current guidelines from the AAP?

It has been posited that the administration of IV fluid in the intrapartum period can affect neonatal weight loss. The assertion is that IV fluid “plumps up” (i.e., causes edema) of the fetus, leading to an artificially inflated birth weight. Diuresis after birth then causes apparent significant weight loss. But babies are not diuresing after birth, as evidenced by their low wet diaper output in general.

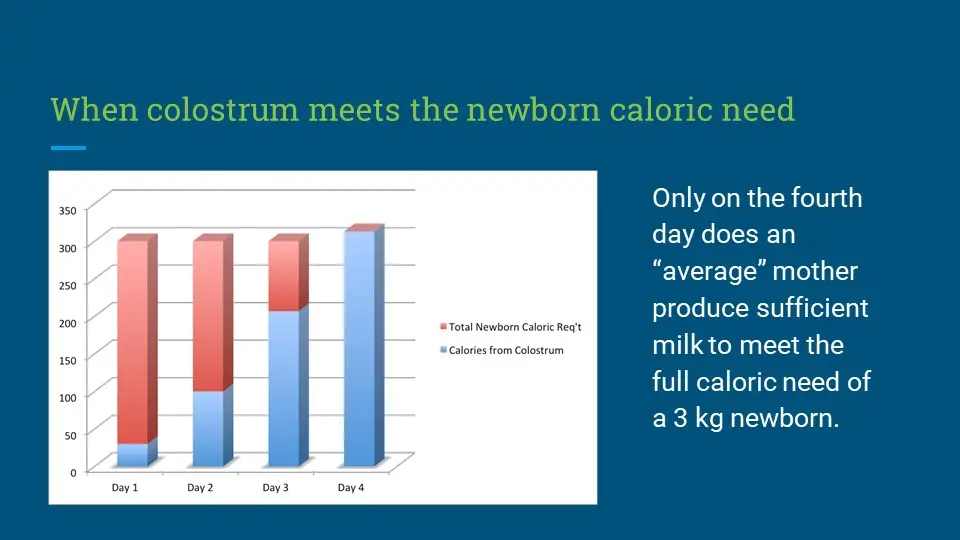

A 2011 study published in Pediatrics (Chantry et al.) sought to examine potentially modifiable factors in excessive weight loss (EWL) in predominantly breastfed newborns. This was a relatively small study of 316 infants with gestational ages between 32 and 40 weeks. The authors looked at a number of factors, including prenatal feeding plan, supplemental feeding, onset/delay of lactogenesis, nipple type, nipple pain, and interventions during labor, including IV fluid administration. They defined excessive weight loss as ≥10% of birth weight by three days of age. Overall, 18% of infants who were exclusively breastfed or received minimal (defined as <60 ml total) supplemental formula had EWL. 19% of exclusively BF infants had EWL; 16% of minimally supplemented infants had EWL, and only 3% of infants who had supplemental feeds of >60 ml total had EWL. To greatly simplify the statistical analysis, the initial analysis showed a number of factors associated with EWL, including higher maternal age and education, hourly intrapartum fluid balance, postpartum edema, delayed lactogenesis, fewer infant stools, and birth weight. Further analysis found only two significant factors: intrapartum fluid balance and delayed lactogenesis. EWL occurred in 30% of EBF/minimally supplemented infants whose mothers had high hourly intrapartum fluid balance, and 10% of those whose mothers had low hourly fluid balance. Around the issue of delayed lactogenesis (defined as not “feeling noticeably fuller” by 72 hours), 35% of EBF/minimally supplemented infants with mothers who reported delayed lactogenesis had EWL; for women who reported no delay in lactogenesis, 8% of EBF/minimally fed infants had EWL.

I can’t help but wonder whether this study failed to see the forest for the trees. A higher fluid balance may be a marker for longer labor and labor complications, which in turn would certainly affect postpartum recovery, fatigue, and lactogenesis. The authors relied on subjective perception by primigravidas as a definition of delayed lactogenesis and reported it as 42%, a much higher prevalence than the usual estimate of 15%. Indeed, the title of this article could have been “Excess weight loss in the first-born breastfed newborns relates to delayed lactogenesis”—not nearly as exciting. The authors themselves advise caution in interpreting weight loss and state that EWL should not be assumed to be fluid loss alone but may indeed represent insufficient feeding.

A later study by Elroy et al. (2017) also sought to examine whether there is a relationship between EWL, type of fluid (colloids + crystalloids or crystalloids alone), and IV fluid dose. This was a larger study, involving 801 dyads. EWL was defined as >7% of birth weight. In this case, the authors did not find a difference in the rate of EWL associated with the type of fluid given, nor did they find a dose-response relationship between the amount of fluid and EWL. As an aside, they mention the confounding variable of maternal hypotension, which of necessity would require fluid administration, but which could lead to impaired uteroplacental perfusion and fetal acidosis, affecting the vigor of the infant.

So do I think that a 7-10% or greater weight loss is grounds for concern? Absolutely. Ascribing excessive weight loss to maternal IV fluid is disingenuous at best.

While IV fluid may contribute to perceived weight loss, this relationship is by no means established, but the relationship between poor feeding and weight loss is. With the exception of critical infants with certain prenatal conditions, I do not see infants born with perceptible edema.

A comprehensive exam for every breastfeeding dyad will include:

- Maternal health. In the aggregate, women giving birth today are older, have higher BMIs, and are more likely to have underlying chronic health conditions or pregnancy complications than women in previous generations. Delayed childbearing means that women may be having children after the age of 35. Older mothers are more likely to have pregnancy and childbirth complications. The obesity epidemic has affected people of all ages and socioeconomic strata; obese women may have underlying chronic health problems such as diabetes and hypertension and may have more difficulty with mobility and healing. Long or complicated labor may contribute to fatigue, which can delay(link) onset of milk production and can also increase the risk of (link)accidental suffocation of the infant. No mother plans to fall asleep with her baby in the bed, but if parents are awake for 36+ hours, their risks for falling asleep while breastfeeding or holding their baby increases.

- Substance use. About 10% of babies in our facility are affected by maternal substance use; about half of these are affected by opioids, whether illicit drugs, prescription drugs, or medication-assisted treatment (MAT) drugs such as methadone and buprenorphine. We can and do support breastfeeding in women who are stable in recovery, even if on MAT, but we recognize that these women may have unique stressors that may make breastfeeding more difficult. Infants who are experiencing withdrawal often have disorganized feeding. Hunger can exacerbate withdrawal, and weight loss is a symptom of withdrawal. These infants do stay in the hospital longer for observation; my threshold to start supplemental feedings is lower since they are at risk for significant weight loss.

- Breast anatomy. A history of augmentation or reduction surgery may impact milk production or transfer. Wide-spaced, “tubular” breasts may be an indicator of insufficient glandular tissue. Flat or inverted nipples may present difficulty with latching; a breast shield may help, but the use of a shield should prompt careful follow up of feeding, milk transfer, and weight gain.

- Feeding assessment. Every breastfeeding dyad should have an evaluation of feeding by a lactation consultant or clinician with expertise. Latch, nipple pain, and evidence of transfer, such as audible swallowing, are one part of the assessment. Can the mother get the baby on independently or does she require assistance? If the nurse has had to get the baby latched for every feeding, the dyad is not ready for discharge.

- Anatomy of the infant’s mouth. Tongue ties and other anatomical considerations may present specific challenges to feeding. (Link) Frenulotomy and lysis of lip ties have become common. Infants who may be at risk for feeding difficulty should be followed very closely, whether or not they have surgical intervention.

- Timing of weight assessment. A 7% loss has different implications depending on the day/hour or age. If the weight was done 16 hours earlier on the evening shift before the morning of discharge, I request a repeat weight.

- Gestational age. Late preterm (LPT) infants are often cared for in the well-baby setting and may masquerade as healthy term infants, but they are not. LPTs may have excessive weight loss; readmission rates for weight loss, jaundice, and other complications are up to three times higher than for term infants. In our facility, late preterm infants are observed in the hospital setting for a minimum of 72 hours. Our protocol for the care of the LPT follows the recommendations of the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine: we initiate supplemental feedings for a weight loss of ≥3% by 24 hours or ≥7% by day 3 or, of course, sooner if there is evidence of hypoglycemia, dehydration, jaundice or poor feeding.

- Birth weight. We assess weight loss by percentage since babies come in many sizes…however, a 7% weight loss in a baby who weighed five pounds at birth looks different than the same percentage in a large infant who has more reserves of fat and glycogen.

- Output. Passage of urine and stool are unreliable indicators of intake, but no or very low output suggests poor intake. A breastfed infant may have only 1-2 wet diapers per 24 hours in the first day or two, but as mother’s milk comes in, the output should increase because of colostrum amounts increase. I always discuss watching output at home and contacting the pediatrician promptly if the infant is not producing urine or dirty diapers.

- Experience. Is this a first baby or has the mother successfully breastfed other children? Did she try breastfeeding before and stop? If so, what were the issues?

- Exam. A physical exam includes an assessment of hydration status: fontanels, skin turgor, mucous membranes, as well as general well-being, suck, activity level.

So would I discharge a baby with a greater than 7% weight loss and no supplemental feedings? It depends on the complex thought process that goes into discharge planning. Every mother-baby dyad is unique and requires individualized care. An EWL baby can decline rapidly in 24 and It’s important to teach parents about what signs to look for insufficient breastfeeding so that they can safely supplement until they have their next day follow-up pediatrician appointment. Weekends pose particular concerns. Discharging a baby on a Monday with an outpatient appointment the following day is a very different scenario than discharging on a Friday of a holiday weekend with no possibility of follow up until Tuesday. In certain cases where risk factors are present, such as LBW or prematurity, I may order outpatient weight checks for a few weeks. As well, follow up with a lactation consultant can be invaluable for the mother who needs support.

Resources: Boies, E.G., Vaucher, Y.E. & the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine (2016). ABM Clinical Protocol #10: Breastfeeding the late preterm (34-36 6/7 weeks of gestation) and early term infants (37-38 6/7 weeks of gestation, second revision 2016. Breastfeeding Medicine, 11 (10).Chantry, C.J., Nommsen-Rivers, L.A., Peerson, J.M., Cohen, R.J. & Dewey, K.G. (2011). Excess weight loss in first-born breastfed newborns relates to maternal intrapartum fluid balance. Pediatrics, 127, e171-9.Eltonsy, S., Blinn, A., Sonier, B., DeRoche, S., Mulaja, A., Hynes, W., Barrieau, A. & Belanger, M. (2017). Intrapartum intravenous fluids for caesarian delivery and newborn weight loss: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Paediatrics Open 2017 (1).

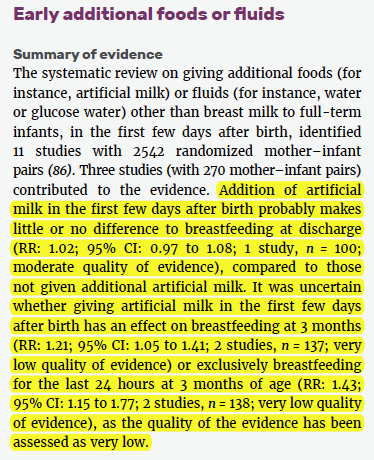

WHO 2017 Revised Guidelines Provide No Evidence to Justify Exclusive Breastfeeding Rule While Evidence Supports Supplemented Breastfeeding

Weight Loss is Not Caused by IV Fluids: The Dangerous Obsession with Exclusivity in Breastfeeding:

Is My Baby’s Weight Loss Normal Or Excessive?

http://fedisbest.org/2019/10/faqs-does-the-fed-is-best-foundation-believe-all-exclusively-breastfed-babies-need-supplementation/

http://fedisbest.org/information-for-hospitals-ensuring-safety-for-breastfed-newborns/informed-consent-regarding-risks-of-insufficient-feeding/

HOW YOU CAN SUPPORT FED IS BEST

There are many ways you can support the mission of the Fed is Best Foundation. Please consider contributing in the following ways:

- Join us in any of the Fed is Best volunteer and advocacy, groups. Click here to join our health care professionals group. We have: FIBF Advocacy Group, Research Group, Volunteer Group, Editing Group, Social Media Group, Legal Group, Marketing Group, Perinatal Mental Health Advocacy Group, Private Infant Feeding Support Group, Global Advocacy Group, and Fundraising Group. Please send an email to Jody@fedisbest.org if you are interested in joining any of our volunteer groups.

- If you need infant feeding support, we have a private support group– Join us here.

- If you or your baby were harmed from complications of insufficient breastfeeding please send a message to contact@fedisbest.org

- Make a donation to the Fed is Best Foundation. We are using funds from donations to cover the cost of our website, our social media ads, our printing and mailing costs to reach health providers and hospitals. We do not accept donations from breast- or formula-feeding companies and 100% of your donations go toward these operational costs. All the work of the Foundation is achieved via the pro bono and volunteer work of its supporters.

- Sign our petition! Help us reach our policymakers, and drive change at a global level. Help us stand up for the lives of millions of infants who deserve a fighting chance. Sign the Fed is Best Petition at Change.org today, and share it with others.

- Share the stories and the message of the Fed is Best Foundation through word-of-mouth, by posting on your social media page and by sending our FREE infant feeding educational resources to expectant moms that you know. Share the Fed is Best campaign letter with everyone you know.

- Write a letter to your health providers and hospitals about the Fed is Best Foundation. Write to them about feeding complications your child may have experienced.

- Print out our letter to obstetric providers and mail them to your local obstetricians, midwives, family practitioners who provide obstetric care and hospitals.

- Write your local elected officials about what is happening to newborn babies in hospitals and ask for the legal protection of newborn babies from underfeeding and of mother’s rights to honest informed consent on the risks of insufficient feeding of breastfed babies.

- Send us your stories. Share with us your successes, your struggles and everything in between. Every story saves another child from experiencing the same and teaches another mom how to safely feed her baby. Every voice contributes to change.

- Send us messages of support. We work every single day to make infant feeding safe and supportive of every mother and child. Your messages of support keep us all going.

- Shop at Amazon Smile and Amazon donates to Fed Is Best Foundation.

Or simply send us a message to find out how you can help make a difference with new ideas!

For any urgent messages or questions about infant feeding, please do not leave a message on this page as it will not get to us immediately. Instead, please email christie@fedisbest.org.

Thank you and we look forward to hearing from you!

Click here to join us!