Written by an anesthesiologist and Intensivist physician

“The biggest achievement of my life as a physician was stopping my hospital’s Baby-Friendly program after my child was harmed.”

It was September 20th, and we were headed to the hospital for my induction. I was nervous, as any first-time mother would be. I was worried that I was doing the wrong thing, even though I knew the literature, and my physicians supported my decision for an elective induction at 40 weeks. I was already dilated to 4 cm and my baby had dropped way back at 33 weeks. We all thought it would take just a hint of Pitocin, but I labored for 24 hours until my son was born. I was later told that he was born with a compound hand (up by his head), causing the prolonged pushing time and his distress with each contraction.

While pregnant, I had decided to attempt breastfeeding, even though I had had a breast reduction in 2003. I tried to read as much as I could, but honestly, I didn’t have any idea how much information one needed to do something that everyone swore was “best” and “natural.” My baby was born at 4:14 a.m. I thought this would be ideal, because I would have the support and help as I learned how to be a mother, knowing more staff were available during the day. As the first day melted into the first night, nursing became more and more painful, and he needed to feed almost continuously. When he wasn’t feeding, he was either rooting or screaming.

When my son was a day old, I noticed that the swelling on his head was much larger than expected at 24 hours out, and it was red and bruised in appearance. We figured out that he had a very large cephalohematoma (a collection of blood between a baby’s scalp and the skull that often happens during a difficult or prolonged birth). Despite the lack of any operative interventions during birth, this happened. Things happen. As a physician, as an anesthesiologist, and now as an intensivist, I know this, but what I still can’t understand is why these six red flags didn’t concern any of my or his providers:

- Breast reduction

- Constant crying

- Excessive weight loss

- Not sleeping/settling after nursing

- Painful nursing

- Cephalohematoma and jaundice

During this first day of my son’s life, a lactation consultant came by to see us. This was requested because of my history of breast reduction. She determined the unbearable pain I was experiencing was likely due to a tongue tie. As this was new territory for me, I assumed that my baby’s care team’s assessment and the plan was correct. As we planned for the frenectomy the following morning, not one person mentioned anything about pain management other than nipple cream. All I heard was feed, feed, feed; don’t you dare fall asleep with the baby; don’t you dare give him a pacifier, and the baby is crying because “he needs to be burped,” “he isn’t swaddled tightly enough,” and “he’s hungry, just feed him again.”

On the second night, the pain wasn’t better despite the clipping. My son had to take his hearing test multiple times because he wouldn’t stop screaming; we couldn’t get newborn photos offered by the hospital because he wouldn’t stop screaming; we couldn’t walk down to the breastfeeding class because he wouldn’t stop screaming; and at one point in time when the LC came back in for another 15-minute session, all she said was “well I don’t know what’s wrong with him.” Daddy, both grandmothers, and I just said yes, ok, and we didn’t think there was anything to do but do what they said: “just feed the baby.”

This is the NEWT tool that is used to track excessive weight loss while exclusive breastfeeding. My son was placed in a very dangerous zone and I wasn’t informed at our discharge.

He lost 8.4 percent of his birth weight at 36 hours of age, but a conversation about supplementation never happened. Looking back, I could just kick myself for not knowing where he fell on the jaundice nomogram (a tool that determines how severe a baby’s jaundice level is). But in this position, I was just a mother, not a physician. And in all honesty, if I didn’t know to ask these questions, then who would? The pediatric nurse practitioner who discharged us came into my room and gave an impassioned and detailed discharge diatribe about exclusive breastfeeding, and about how I should spend all of my time topless and feeding constantly until my supply was established. So on Wednesday afternoon, we went home with a follow-up clinic appointment 36 hours later with no mention of supplementing, despite all of the very dangerous red flags.

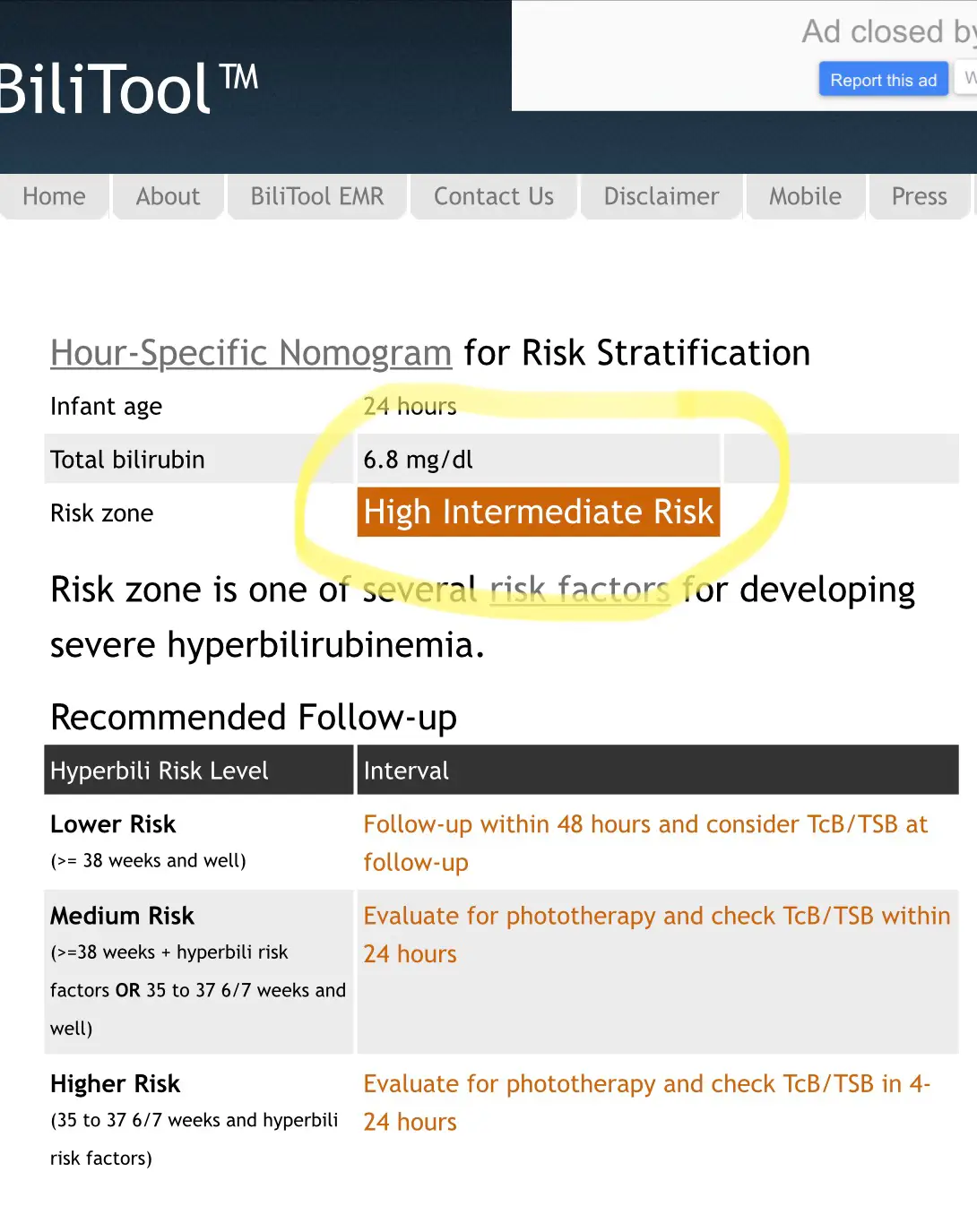

At 24 hours of age, my son had a high intermediate risk for hyperbilirubinemia using the BiliTool.

The next 36 hours were pure hell. Absolute misery. My newborn would not stop crying…ever. I would just latch and latch and latch, bleeding, crying, and at one point in time missing a small part of my left nipple. The grandmas wanted desperately to give a pacifier and help feed him, but it had only taken 48 hours in the hospital and the raw fear of new motherhood to turn me into an avid exclusive breastfeeder. They said I should do this so I have to do this. I follow the rules, I do what is best, I am a doctor, I have to do this, they said I had to…it was a spiral.

We found out if we pushed him in the stroller fast, he would stop crying temporarily. I was four days postpartum, in my pajamas, practically running around the neighborhood trying to not have to breastfeed my baby for at least a little while—because I just couldn’t anymore. After an aggressive stroller walk, he became listless and was not actively screaming. I convinced myself he had cried himself out and needed rest. I cringe to think what his blood sugar level might have been at that moment.

That night was astronomically worse. I was feeding continuously and I knew this wasn’t normal, so I called the breastfeeding support line and it went to voicemail. I got online and tried calling breastfeeding support groups. No one answered. His father took him outside and walked up and down the street over and over again, but he kept screaming, and we were afraid we would scare people. So we just continued to feed, feed, feed, feed. It had now been five days since I last slept.

The next morning we were at his follow up appointment. His weight loss was down to 9.7 percent and his transcutaneous bili was very high, and they had to send a blood test. While there I met with the LC who attempted to have me pump with miserable results. Her response was literally, “that is all?” We fed him those few MLS in a syringe and for the first time he settled down. But the lab test resulted in immediate readmission for bili lights. His total bilirubin was 21—a number that I will never forget. A number that is as infuriating as it is horrifying. But what is so dumbfounding in retrospect is that not one person thought to check his blood sugar or sodium levels at that time, or at any time during his hospitalization. If only I had had the capacity to use my doctor brain then, but I simply couldn’t. I was just trying to survive.

The crazy thing about all of this though, was that since he had not lost over 10% of his birth weight, they did not insist on supplementation. And since I was still in “follow orders” mode and could not string together a coherent sentence, I thought I should continue to exclusively breastfeed. I was judged and admonished by the pediatric nurses for this because now I was “one of those mothers,” when really I was just trying to be who they wanted me to be on the postpartum floor.

At one point in time, I crouched behind the bili light bassinet and broke down and cried.

Somehow over the next 36 hours, I was convinced to supplement with a bottle under the bili lights. The LC who came by to do a weighted feed scoffed at this and left, while the pediatric nurse yelled at me because I had left two drops of blood on the bathroom floor, and told me to clean up after myself. I had somehow failed at every aspect of new motherhood, and I just wanted to go home.

We went home and tried to breastfeed for one more day, hoping my supply would increase. It didn’t. I exclusively pumped after that, which only ever resulted in 2–3 ounces total in 24 hours. We followed up for another bili check, and he improved dramatically once he was fully fed with formula. I called the LC clinic one last time, but when they suggested I utilize an SNS to supplement, I knew that direct breastfeeding was simply not going to happen. I did however go see my OB because of my bleeding, to make sure that I didn’t have any sort of retained placenta to “blame” for my measly supply. I did not. I simply didn’t have breast milk. I stopped pumping at six weeks because you can only pump for so long for all of 2–3 ounces a day.

When he was about four weeks old, I was pumping and googling and came across a video created by Dr. Christie regarding insufficient breast milk intake and the risks associated with it. As I watched this presentation, I started crying because I felt like she was telling my story, and I was overwhelmed with emotion. I was dumbfounded. I could not believe the risks associated with what had happened to us. I needed to reach out. And so I did.

From there I started to peripherally follow The Fed is Best Foundation. I felt emboldened to fill out a survey of my experience at the hospital. I received a call back from the nurse manager. I gave a detailed account and offered to come and talk to their breastfeeding focus group. She seemed receptive, but I was never asked to come to this meeting. It was at this same time that I was learning more about the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative through the Foundation. I was shocked to find out that the hospital we delivered at was applying for this certification. I had no idea.

You see, the part of this story that is unique is that this hospital was my hospital. I had worked there as a physician in some capacity for seven years at the time my baby was born. This was my medical home. These were my people, and I was shattered that this happened to me…to us…in the place I loved so much.

I tried to work through it personally, but when my baby was four months old I knew I had to do something else. I had to. I knew I couldn’t let this go.

You see, in my life as a physician, I was a passionate patient safety advocate and spent almost as much time writing and implementing policy as I did performing clinical anesthesia. I had personally implemented two patient safety programs in this hospital over the three years prior to my son’s birth. I knew how to adopt a new policy or program, while also confirming that unexpected or unusual complications did not occur out of proportion to the benefit of the program.

So I went to my best friend. A woman who was my peer, my boss, and the strongest woman I know. I broke down with raw emotions to her and asked her for guidance. She led me to the hospital’s patient advocate director, and that is where this story takes a beautiful turn.

She and I pored over our medical records. She arranged for me to meet with the nursing staff, the pediatrician who admitted my son to the hospital, and—the most terrifying—with the physician who had brought the BFHI to our hospital. These meetings were nausea-inducing and difficult. But in dissecting the records and talking through everything with them, I was able to build a case worth taking to our hospital leadership. I was granted a personal meeting with the Executive Officer of the hospital and brought with me my story and lots and lots of medical literature supporting my concerns about safety. In the end, we decided to abandon our BFHI accreditation application.

I continue to be involved with the Fed is Best Foundation, though I often try to stay behind the scenes due to the nature of my profession and the viciousness of the online community. My contribution is mainly through following and reviewing the literature and posting passionate and honest posts on my Facebook page so that other women can derive strength and validation from my story. Through my work with Fed is Best, I now know far more about breastfeeding than I ever knew before, and I was able to safely provide breastmilk for my second child when she was born. I also advocate and support all women in their breastfeeding goals, and provide them with safe resources when they need help that I cannot provide.

This organization is not about demonizing exclusive breastfeeding or glorifying formula. It’s about feeding our children and avoiding preventable complications from insufficient breast milk intake.

Please join our Health Care Professionals Advocacy Group

U.S. Study Shows Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative Does Not Work

Letter to Doctors and Parents About the Dangers of Insufficient Exclusive Breastfeeding

Two Physicians Describe How Their Baby-Friendly Hospital Put Their Newborn in Danger

Nurses Quit Because Of Horrific Experiences Working In Baby-Friendly Hospitals

Nurses Are Speaking Out About The Dangers Of The Baby-Friendly Health Initiative

Neonatal Nurse Practitioner Speaks Out About The Dangerous Practices Of The BFHI

NICU Nurse Discloses Newborn Admission Rates From Breastfeeding Complications in BFHI Unit

My Baby Had Been Slowly Starving – The Guidelines For Exclusive Breastfeeding Were Wrong

The Medical Professionals At The University Of North Carolina Allowed My Baby To Starve

I May Never Forgive The Hospital For Starving My Baby While Under Their Care!

Just One Bottle Would Have Prevented My Baby’s Permanent Brain Damage From Hypoglycemia

Read the Stories of Thousands of Families, Nurses and Physicians Who Signed the Fed is Best Petition

5 thoughts on “Hospital Drops Baby Friendly Program After Doctors Baby Was Harmed”